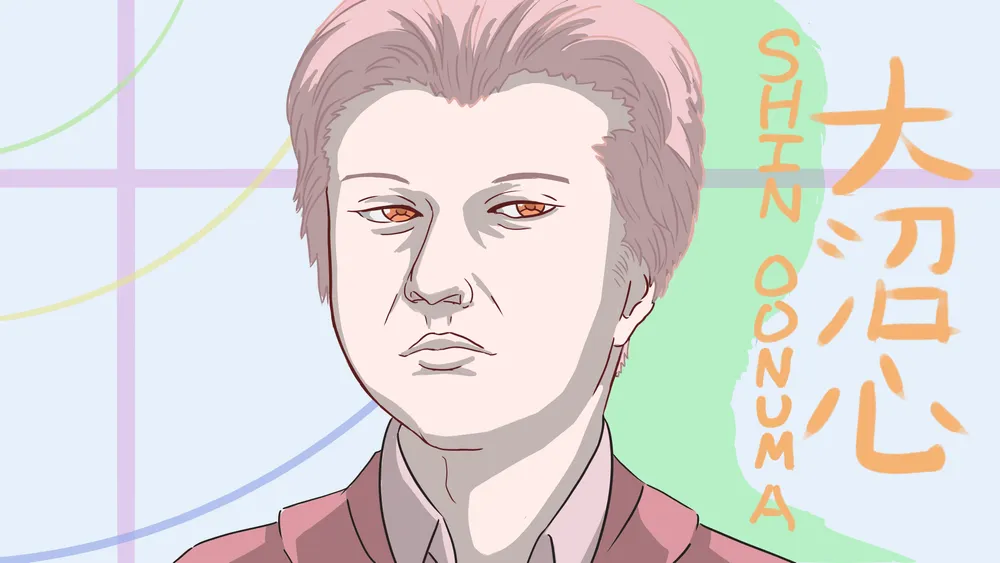

The Work and Legacy of Shin Oonuma

Of the three directors who made up “Team Shinbo”—a designation describing a trio of directors consisting of Akiyuki Shinbo (新房昭之), Tatsuya Oishi (尾石達也), and Shin Oonuma (大沼心)—I think that Oonuma is the most underappreciated. Shinbo’s gothic aesthetics, bold use of color, and esoteric staging tendencies secured his status as one of anime’s most interesting directors; and Tatsuya Oishi’s tour de force adaptations of Nisioisin’s Monogatari series and his foundational influence on SHAFT’s "house style", have likewise secured his legacy in the annals of the studio’s history; but Oonuma, on the other hand, has received less recognition when it comes to both his abilities and his importance to the foundation of SHAFT and later SILVER LINK.

In the mid-to-late 2000s, although slightly overshadowed in the western sphere due to Shinbo’s name appearing in the main “director” credit across most of SHAFT’s series, Oonuma ascertained a level of prominence as a rising director. Speaking about his time with SHAFT, director Ryouki Kamitsubo (上坪亮樹) once referred to himself as being like a swordsman and compared both Oishi and Oonuma as being like assistant instructors with Shinbo acting as a head instructor. It's a humorous analogy and not meant to be taken as an explicit comparison, but it's an easy way of understanding the core ideas and people that the studio was operating around.

Whether it be due to dissatisfaction with much of his recent work as a sort of mentor-like figure at SILVER LINK, or just a generalized opinion that Oonuma’s stylistic qualities aren’t as ubiquitous and mentionable as the other two giants he was paired with for the better part of half a decade, he’s outright underrecognized–otherwise, I don't think people like Kamitsubo would use illustrious language to describe him favorably with his contemporaries. I want to talk about Oonuma and his works: the good, the bad, and the disappointing, as well as his influence on those who have and continue to work with him, and his directing as a whole.

Early Career (1997-2004)

Born in 1976, Oonuma is the youngest of the Team Shinbo trio, being six years Oishi’s junior and 15 years younger than the group’s eponymous leader. He didn't have much of an interest in anime as a child, and instead was a gamer obsessed with the Famicon, which was released around the time he was in elementary school. It wasn't until late high school, when he had vague aspirations of entering the entertainment industry because of his adoration of games, that he started to watch a lot of anime. One particular anime that connected with him was Tenchi Muyo! Ryo-Ohki (1992-1993), which inspired him to join the anime industry. Up until then, he ignored drawing and didn't want to do it because his mother was a former manga artist and illustrator, and his brother was good at drawing, whom he didn't like being compared to.

Around 1997, he joined Office AO, where one of his first credits include being a douga (in-between and trace) animator on Berserk. Although young in his career, Oonuma was quickly given the responsibility of layout artist and key animator, doing such on productions like Silent Mobius only a year after Berserk. However, as the years progressed, he felt that his desire to continue drawing became “weaker and weaker,” and eventually he fell out of love with being an animator. At some point, he went freelance from Office AO, and in the early 2000s he was given the chance to work as a director.

Although I was previously under the impression that Oonuma's first call to directing was with Shinbo in 2003 prior to their work at SHAFT, he actually directed an episode in 2002: episode two of the hentai OVA Mizuiro under the late Shigeki Awai (粟井重紀) at studio ARMS. The OVA's quality is rather lackluster, but there are a few interesting moments.

Mizuiro, ©2002 NEKO NEKO Software/Pineapple Project

Contextually, Oonuma's work on Mizuiro makes a lot of sense because Shinbo mentioned in an interview that he heard about Oonuma and his digital processing skills, thus why he asked Oonuma to work with him—and Oonuma didn't agree with that assessment of his ability, but he took on the job anyway.

The two's first job together was the second episode of Nurse Me!—another hentai—produced at Arcturus (essentially the same company in practice as Seven Arcs but slightly predating it) and with Shinbo under the penname "Juuhachi Minamizawa." During this era, directly succeeding his work on The SoulTaker (2001), Shinbo was focusing his efforts at Arcturus: first directing a segment from the Triangle Hearts: Sweet Songs Forever Sound Stage VA that later spawned Masaki Tsuzuki's Magical Girl Lyrical Nanoha spin-off franchise (2004-present); and then working on several hentai.

Arcturus is an interesting studio in that they were open to heavy experimentation in artistic endeavor utilizing early CG and digital photographic processing across all of their works, which Shinbo was privy to. Part of this was because of integral members of Arcturus like Keizou Kusakawa who brought along various experimental ideas and processes, especially in regard to 3DCG and digital processing.

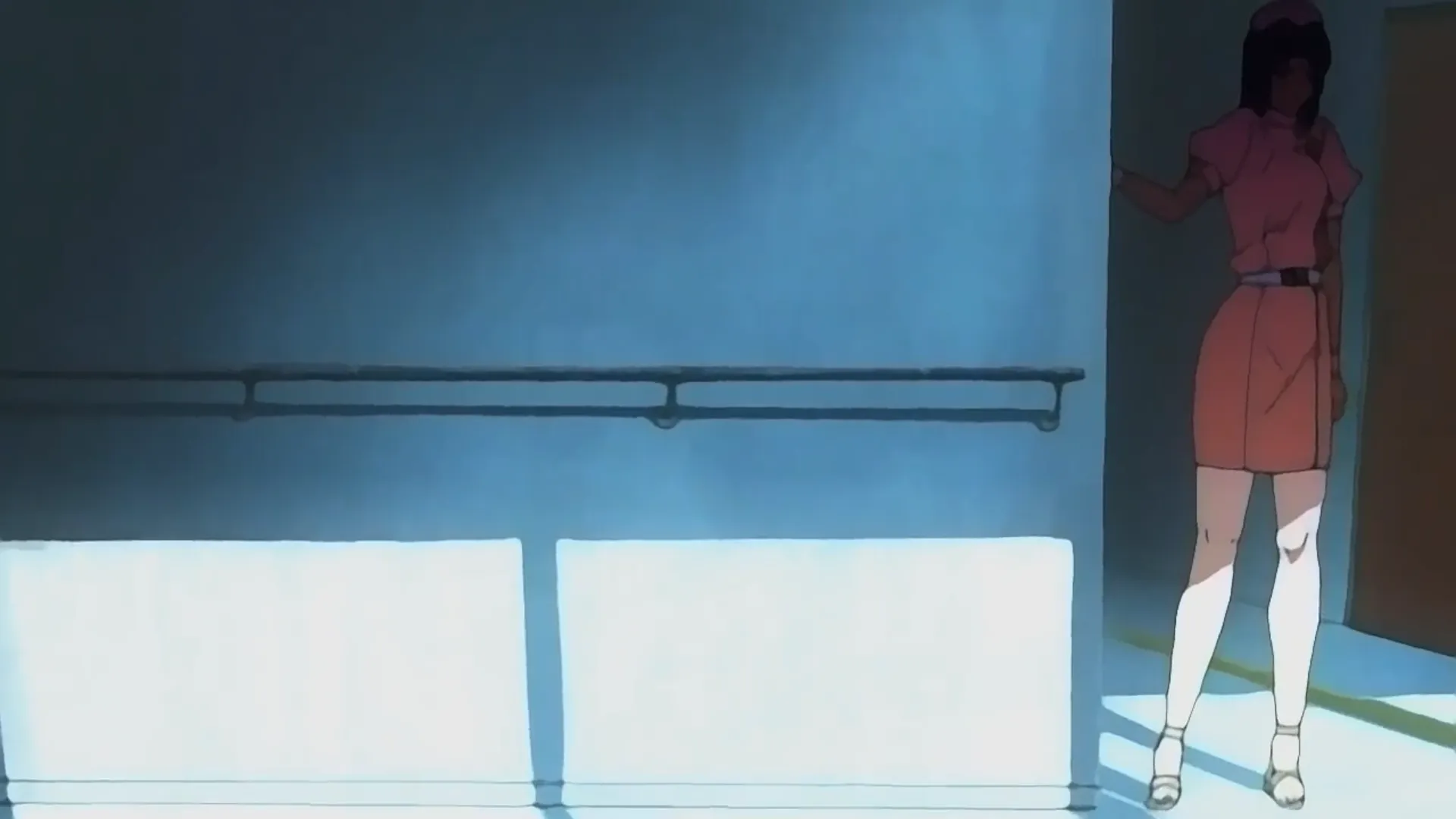

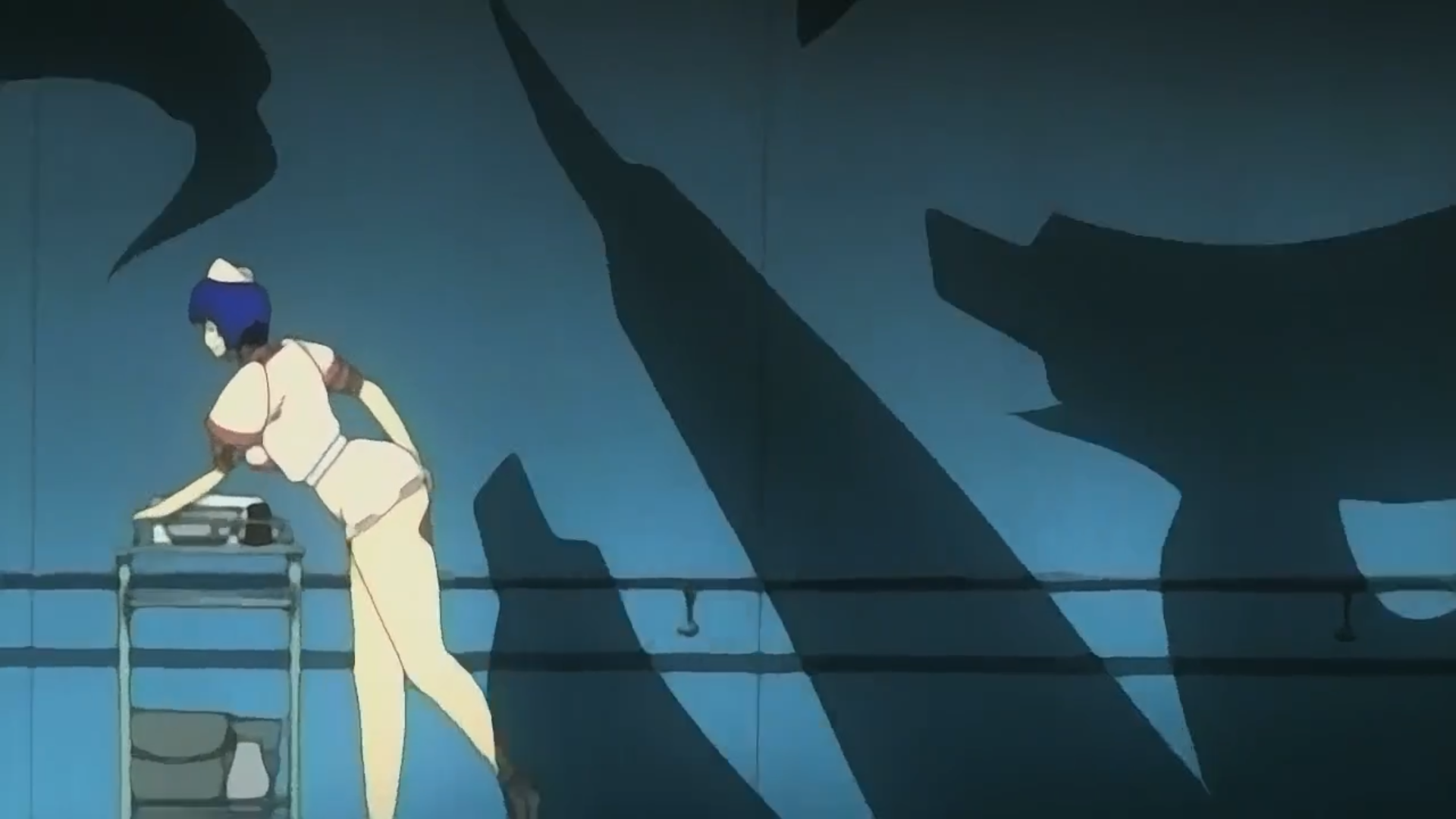

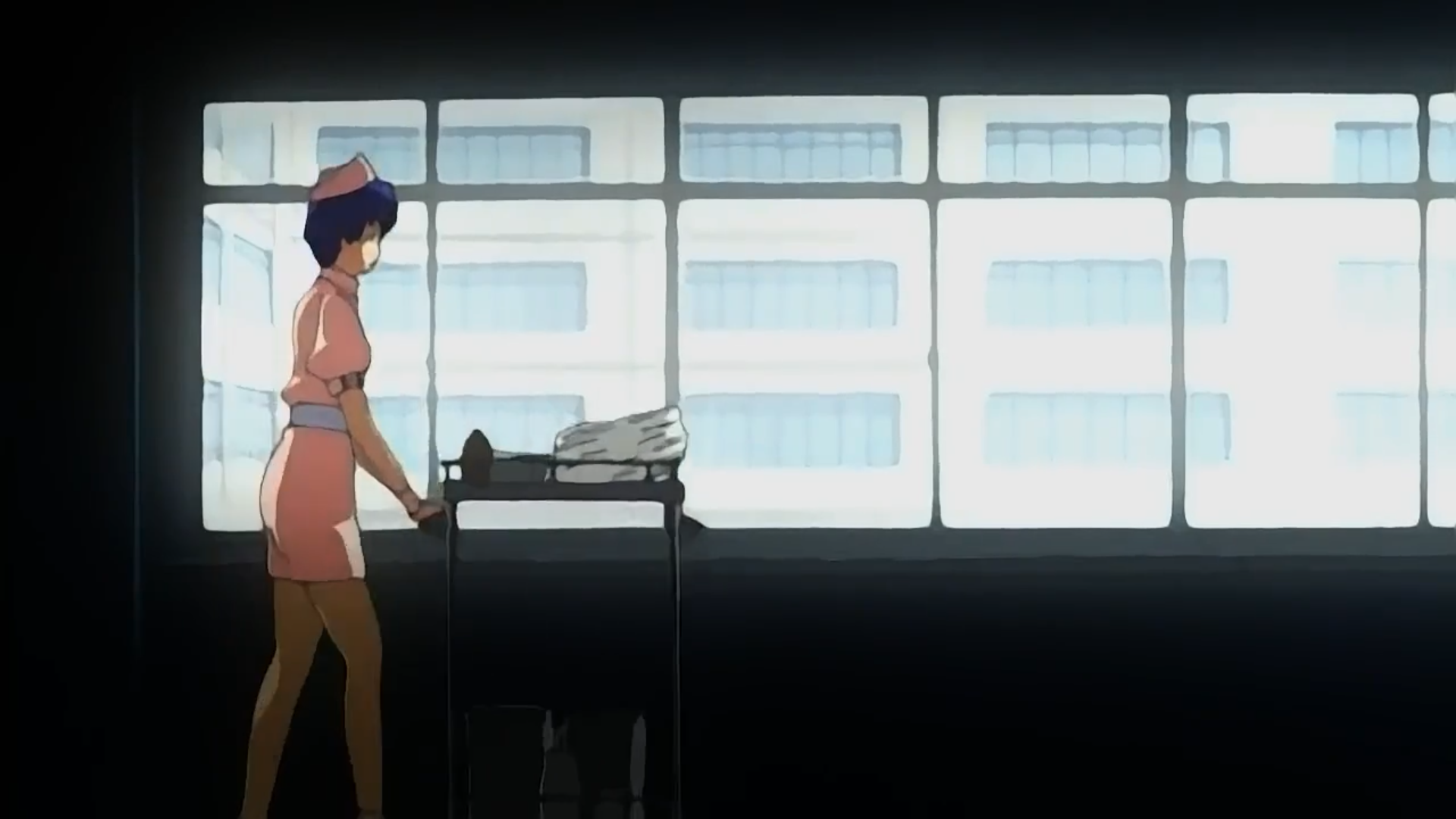

Nurse Me!, ©Anim / Discovery

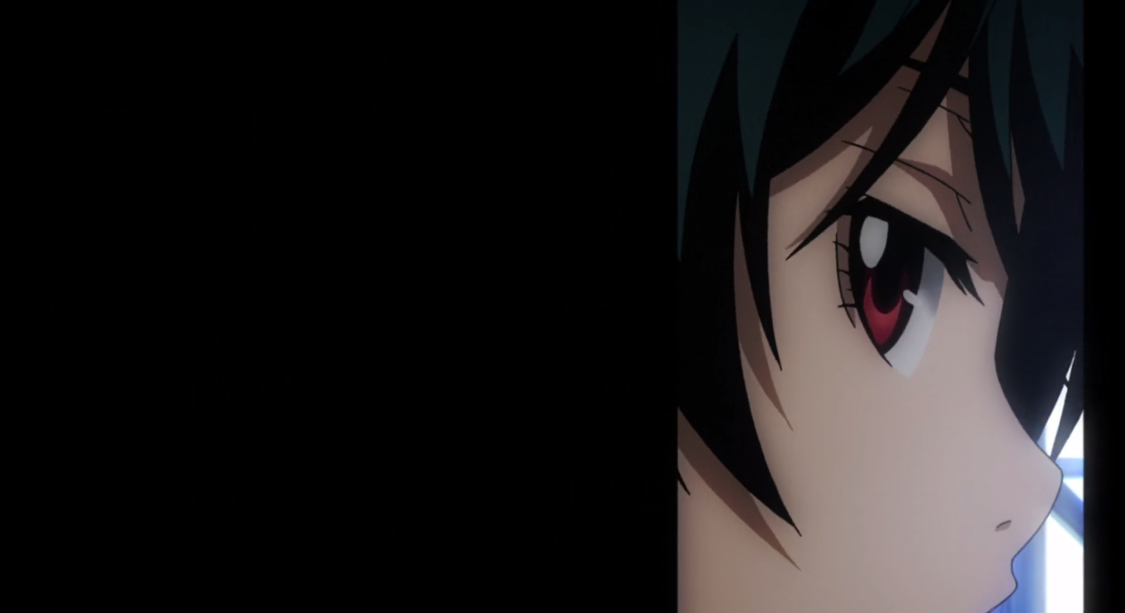

The second episode of Nurse Me! credits no storyboard artist, but it's presumed to simply be the work of Shinbo given the style. It's difficult to tell exactly what Oonuma's specific contributions might have been, but it's undoubtedly well-directed bringing out a strong sense of oppression that Shinbo's storyboards for these kinds of works, which depict toxic or abusive relationships and actions, often have. Draped shadow gradients and heavier lighting aesthetics are tempted by voyeuristic, often low-angled, "hidden" cameras. Though Nurse Me! isn't entirely "oppressive," the screenplay also gets pretty goofy, and the direction reflects that when necessary.

This is a work that includes tumultuous subjects of abuse, unwanted actions, the desire to "help" people (in the context of a nurse), religious connotations (that, as far as Anim's website indicates, was not in the original game), and perhaps even connotations of sexual repression and discovery; there are are clear visual motifs revolving around "light/dark" and "shadows" around how these characters exist within this fictional context.

Nurse Me!, ©Anim / Discovery

Over the next year, Oonuma directed at several different places: he directed episode 9 of Futari no Spica (2003) at Group TAC and episode 10 of Wind: A Breath of Heart (2004) at RADIX. Also in 2003, Shinbo gave him the opportunity to co-storyboard (with Hiroyuki Shimazu) the third episode of Triangle Heart: Sweet Songs Forever, which Oonuma directed and also contributed key animation for. In 2004, he astoryboarded and directed the first episode of Hourglass of Summer (Natsu-iro no Sunadokei) under director Takahiro Okao at Picture Magic and Rikuentai, and subsequently directed the second episode as well.

Again, it's difficult to say exactly what Oonuma was responsible for on his episode of Triangle Heart since his specific flavor of directing was not yet developed, he worked under a "prime Shinbo", and co-storyboarded the episode with someone else.

Triangle Hearts: Sweet Songs Forever, ©Ivory, Janis / Discovery, King Records

As for Hourglass of Summer, elements of Shinbo's influence on Oonuma protrude mostly in the first episode, given it's the episode Oonuma had control over as both episode director and storyboard artist. Flashes of monochromatic colors (specifically red) acting as visual beats appear, as do negative spaces and framed images, voyeuristic Dutch angles, and flatter screen design choices.

Hourglass of Summer, ©2004 PrincessSoft/KSS, Picture Magic

SHAFT Era: Team Shinbo (2004-2009)

SHAFT's first president retired in 2004 and then-managing director Mitsutoshi Kubota (久保田光俊) succeeded him. This era of SHAFT saw the studio expand its internal production capabilities with the addition of a photography and visual effects department. Another change was that Kubota wanted to establish the company with a unique brand, and to that end, he looked for a director to work with in a special capacity. Shinbo planned to make something with SHAFT through Nippon Victor producer Hiroyuki Birukawa because the director liked SHAFT's outsourced episode of The SoulTaker in 2001.

Shinbo was to be busy with two other projects at two other studios at the same time (Daume and Seven Arcs), but the plan went ahead and Tsukuyomi: Moon Phase was born. The director asked several previous affiliates and colleagues to participate on the show including Oonuma who joined SHAFT alongside him. Probably due to his work elsewhere, Shinbo donned the role of "chief director" for the series (and for the first time in his career), and Toshimasa Suzuki, by then a freelance director but former animator at SHAFT, was given responsibility as the director's assistant to manage the on-site work at the studio. Oonuma was given the responsibility of directing the first episode, which was storyboarded by Shinbo (without credit).

The first episode of the series is an example of his abilities rather than his individual qualities as a storyteller. The overwhelming presence of Shinbo's gothic aesthetics and driving power rule, but Oonuma had a big part to play in another key aspect for the series. Shinbo said he doesn't quite get "moe"–at the very least as far as appealing to "moe." Oonuma, though, is a "gal game" and "moe anime" fan, so Shinbo got help from Oonuma (and other staff members) in solidifying the show's appeal to moe largely in the form of depicting Hazuki (the heroine).

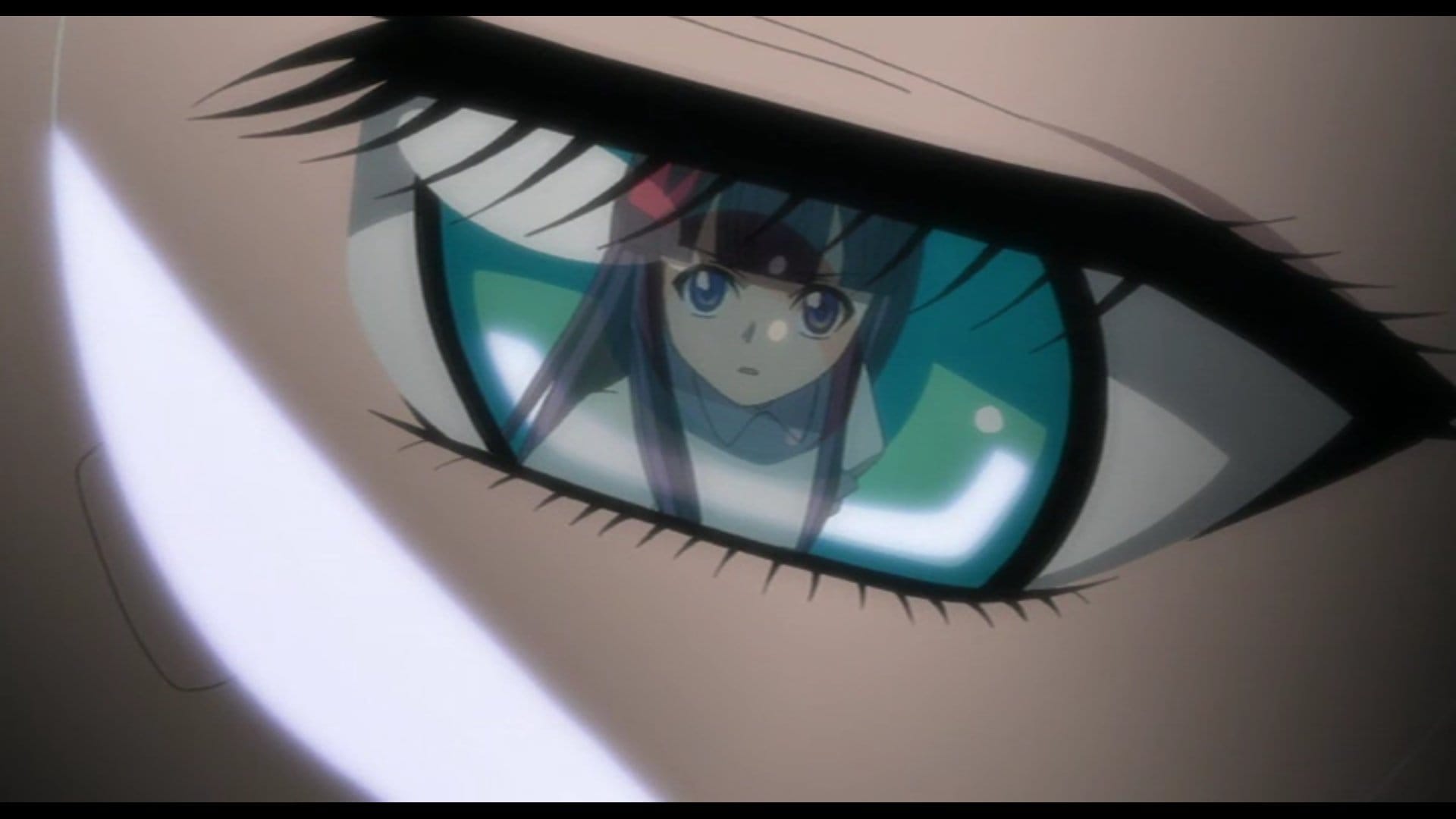

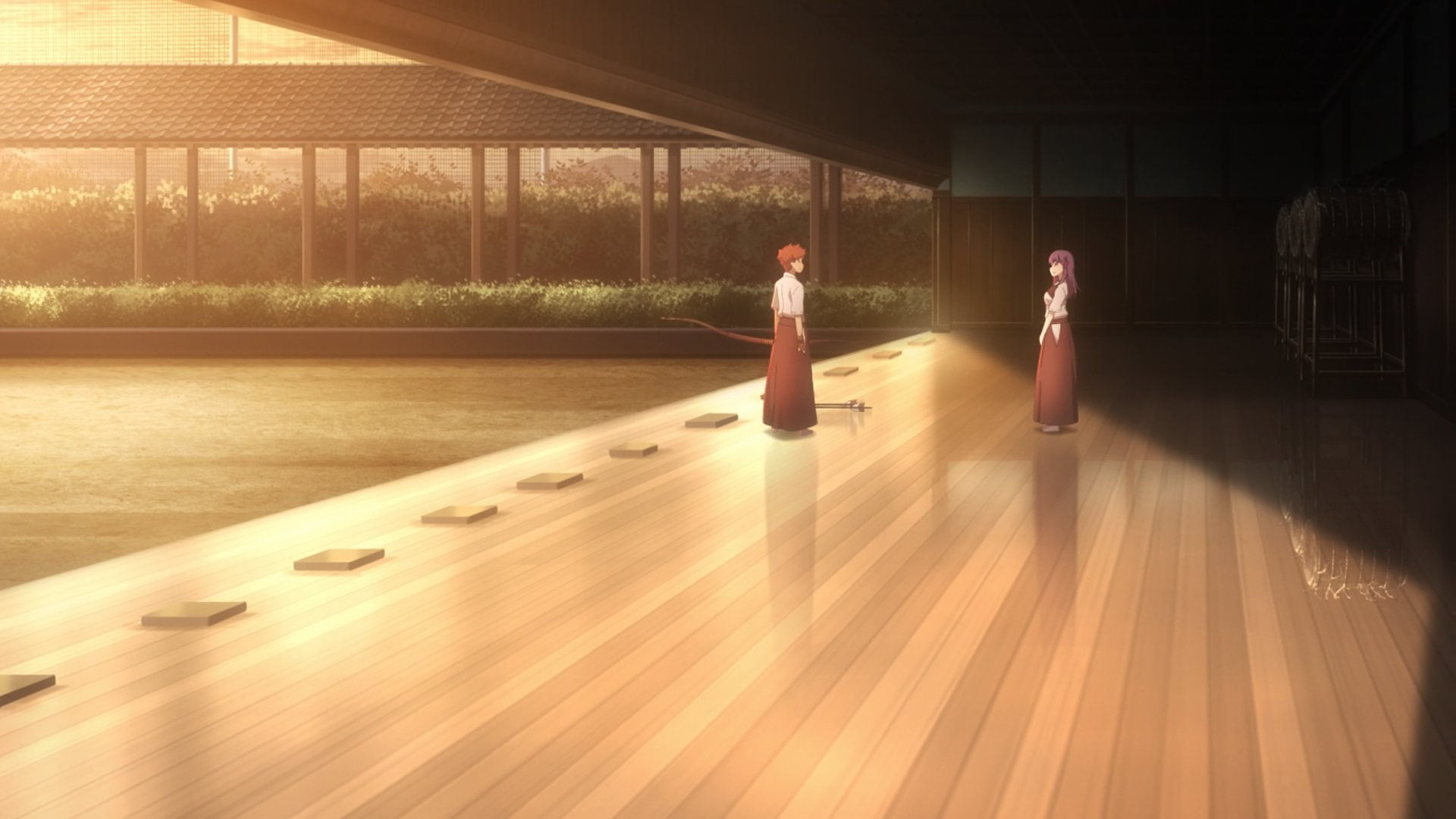

Tsukuyomi: Moon Phase, ©Keitaro Arima / Wani Books, Victor Entertainment

In the meantime, another director who had a desk at SHAFT for about a decade (if you include the days he was subcontracted to them via GAINAX), Tatsuya Oishi, was also given the freedom of directing under Shinbo on the series, and the three became eponymously known as the aforementioned "Team Shinbo." Eight of the series' 26 episodes (episode count including the DVD special) were directed by the two of them, with Oonuma having done five total episodes and also having supervised the DVD retakes and corrections for episode 9.

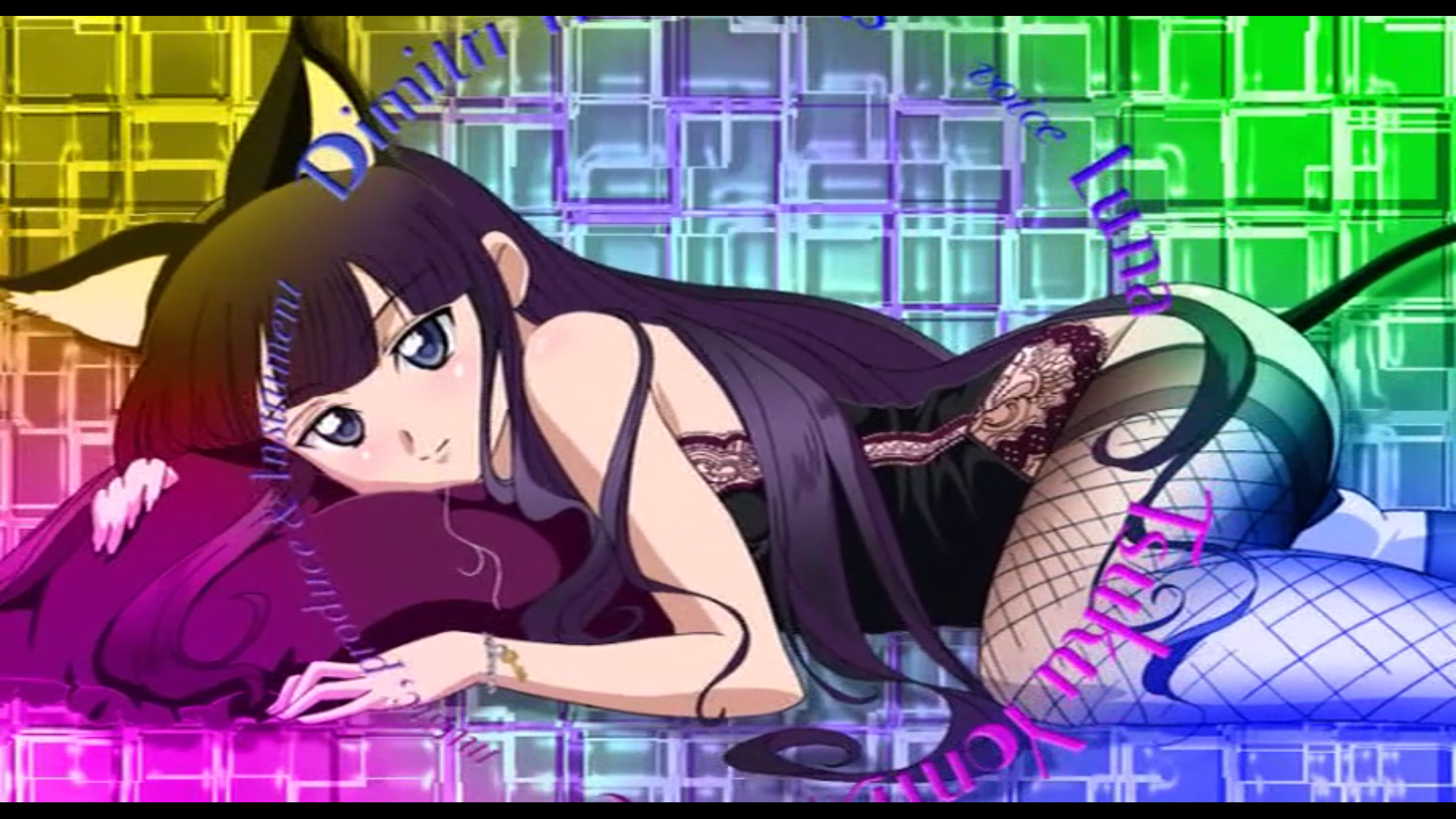

Episode 7 was directed and storyboarded by Oonuma and features a segment where the opening plays and Hazuki does a little fashion show. It's mostly still images featuring Hazuki in various outfits with text floating behind her. Moe fashion aside, this episode is a significant moment for her and the protagonist, Kouhei, as it drives the first major conflict between them. Some of Shinbo's storyboard corrections and advisements are to be expected, but it is a distinct style from episode 1. Its visual language focuses on a theme of perspective, done by showing Kouhei's inability to see Hazuki's perspective and vice versa through both the script and Oonuma's direction of the screen elements. He takes great care to use shaky cams where it's most effective, and so much of the screen composition is made to physically separate the characters, literally reflect them, and exemplify how it is that they see the world around them. As Hazuki loses faith in her friends, their faces are ignored by the camera's lens—either cut off by the framing or draped in a black gradient and thick shadows obfuscating their details aside from their shape.

Tsukuyomi: Moon Phase, ©Keitaro Arima / Wani Books, Victor Entertainment

Another important part of Oonuma's development is that he made special openings for episodes 9 and 14 featuring a song unique to them. The fashion OP segment in episode 7 is kind of like an early prototype of these, considering how it utilizes the same fundamental idea. Like the dress-up segment, both versions of this OP are primarily only a handful of drawings. It's not resource intensive as most of these drawings are completely still besides shifting them across the plane (camera). Color gradient overlays, text, and real-life imagery are also used.

Cost-cutting techniques prevailed during the time of Team Shinbo’s reign at SHAFT, and it was Oonuma who headed this in a materially minimalist-esque sense, regardless of resource capability and intensiveness. Although unopposed to using more resources and dynamic sequences, Oonuma's Tsukuyomi openings accentuated his ability to work with relatively little and still make it interesting. Further down the line, text is a motif in the thematic accentuation of his openings as he expanded into elements like song lyrics and repeating iconography.

Tsukuyomi: Moon Phase, ©Keitaro Arima / Wani Books, Victor Entertainment. Openings from episodes 9 (1-3) and 14 (4-6).

Oonuma was the first director promoted under Shinbo to a "series director" position (honorable mention to Suzuki for Tsukuyomi for holding down the fort, though) with Pani Poni Dash! in 2005. Shinbo retained a position as a standard "director" above Oonuma, while the latter now had responsibility of overseeing episodes that weren't his and elements of the show as a whole, alongside his own episodes. There's also 3 episodes in the second half of the series where Oonuma was given a "supervisor" (監修) credit, but the implication of what that means as opposed to "series director" is vague or even impossible to guess without some sort of anecdote about the circumstances.

This series is the quintessential form of SHAFT. Oishi’s openings solidified his extravagant uniqueness among the newfound staff at the studio, and together with Oonuma’s style of comedy and slowly forming adjacency of a directing style, solidified what was truly "SHAFT style" in combination with the emblematic ideas and freedoms that ringleader Shinbo was responsible for. Anime Style editor-in-chief Yuuichirou Oguro, a longtime viewer and friend of many of the directors and animators from around the studio, considers it to be the purest form of SHAFT.

While Oishi eagerly sprinted down the track to show off his strange colors to the audience, Oonuma needed a little bit of a push. It wasn't until he watched Yasuo Ejima’s 4th episode of Pani Poni, and then Oishi’s succeeding 6th episode, that he felt inclined to take interesting ideas from his peers and make them his own. One such example is Oonuma’s distinctive vision for colors that are neither too bright nor too mellowed out in contrast with each other, which is to say that his color direction is highly noticeable and attractive and yet the individual colors rarely fight for attention of the screen. In moments where pop-like colors are put up against each other, they're never quite battling for control to the degree of the ostentatious color sensibilities of both Shinbo and Oishi’s works that push out a war between bright yellows and bright reds all at once. Another technique Oonuma started to pick up from Shinbo was the use of eyecatches to create and adjust a sense of tempo, which helps episodes have more compressed and natural movements of tempo.

Pani Poni Dash, ©Hekiru Hikawa / Square Enix, Pani Poni Production Committee

In a manner more similar to Shinbo than Oishi, Oonuma stood as keen on collaborating with all of the staff to improve on, create, and process storyboards and ideas. He desires the staff’s creative voices to be heard; for example, animator and later director Naoyuki Tatsuwa (龍輪直征), who actually joined SHAFT because he wanted to work on Pani Poni, was cited as one of the staff members Oonuma went to when it came to making parody gags and jokes.

After Pani Poni, Oonuma was put in charge of Negima!? in the similar-ish role of "chief director" (チーフディレクター), which historically meant more or less the same as the usual "chief director" (総監督) credit but is today used as a sort-of cross between an "assistant director" and "series director" (credits are just generalizations after all, their use is logical yet still arbitrary to a point; please read under the "Negima!?" section in this article for a more detailed overview of this specific credit). Like Pani Poni, the series was important for the vitalization of the studio’s staff and creative power, with new members like Yukihiro Miyamoto (宮本幸裕) making their first appearances and existing staff like Oishi continuing to further their visions.

Negima!?, ©Ken Akamatsu, Kodansha / Kanto Magic Association, TV Tokyo

One of Oonuma's unique early experiments is shifting frames, in which frames themselves move around the screen without being tied down to any specific space besides the boundaries of the screen itself. The content of the first episode, as an expository piece, introduces the audience to a large selection of the (large) cast that flows well in introducing each with their own personality through the screenplay, Oonuma’s visual emphasis, and an otherwise straightforward setup. While I may not know exactly how much Shinbo corrected at the storyboard stage for the first episode, or the series at large, it’s worth noting that the Shinbo-kei visual language stands strong through techniques like foreground object blocking/smacking and the gothic elements in art design which Oonuma picks up on; that is to say, who is responsible for what decisions gets a little muddy; but Pani Poni is no Tsukuyomi, so it's unlikely that any episodes have as extreme corrections by Shinbo.

In utilizing resources for any project, Shinbo once said that much of his stylistic experimentation at SHAFT was the result of needing to limit resource usage and organize them in a way that could allow for striking imagery to exist without compromising too much on quality, like how Oishi originally started to use live-action photography to get away from bad drawings of objects (note: the technical inspiration for him there is American animator Tex Avery's work). Shinbo and the staff's philosophy was working not within but around the limitations of what the industry and studio could allow, which Oonuma takes with him throughout his career post-SHAFT. In episode 14 of Negima!?, there's a nearly two-minute-long, dynamic, constantly moving oner (one cut), the result of which Oonuma said was only possible due to the fact that key animator Genichirou Abe (阿部厳一朗) was not only on staff, but that enough time could be allocated for him to work on that ambitious sequence. The ambition of the scene itself, from a storyboarding perspective, only exists because of the availability and reliability of such a staff member; otherwise, we can suppose that this scene would never have been storyboarded that way.

Negima!?, ©Ken Akamatsu, Kodansha / Kanto Magic Association, TV Tokyo

Following Negima!? and a two-episode OVA, Oonuma got more freedom for his adaptation of Ef: A Tale of the Two, a series historically interesting as SHAFT’s only adaptation of a visual novel during the Shinbo era, and their second visual novel adaptation overall (following Popotan in 2003). Rather than sit in the chief director’s chair, Shinbo sat even further back as the "supervisor" and gave total directing power to Oonuma. Shinbo's role extended as far as giving directing guidance to Oonuma and looking over the screenplay and storyboards, as well as storyboarding one episode himself, which Oonuma directed and considered to be a big help.

Since Oonuma is a big fan of the kinds of works Ef is based on, it makes sense that he was given charge of such an adaptation; and although continuing many of Shinbo’s visual and narrative traits, it remains a product of Oonuma exemplifying his veracity as a director. From its intense dramatic moments to his ability to convey emotion throughout each of the characters’ stories, Ef is the final piece of Oonuma’s evolution and variety, having started with the Pani Poni gag comedy and the romcom drama harem Negima!? His work on Ef even influenced Shinbo, who said that the combination of Ef's serious drama with cute, beautiful girls influenced the later Madoka Magica series.

Shinbo had Oishi direct all of the main openings to both Pani Poni and Negima!?, which early on set him apart from the other SHAFT directors; and while Oonuma contributed special openings to Tsukuyomi and Negima!?, not to mention being in charge of both 2005-2006 period works as series/chief director, Hidamari Sketch and Ef (both 2007) were the first time that he directed openings that were to be used for the full broadcast of a series (in other words, not just special one-off openings).

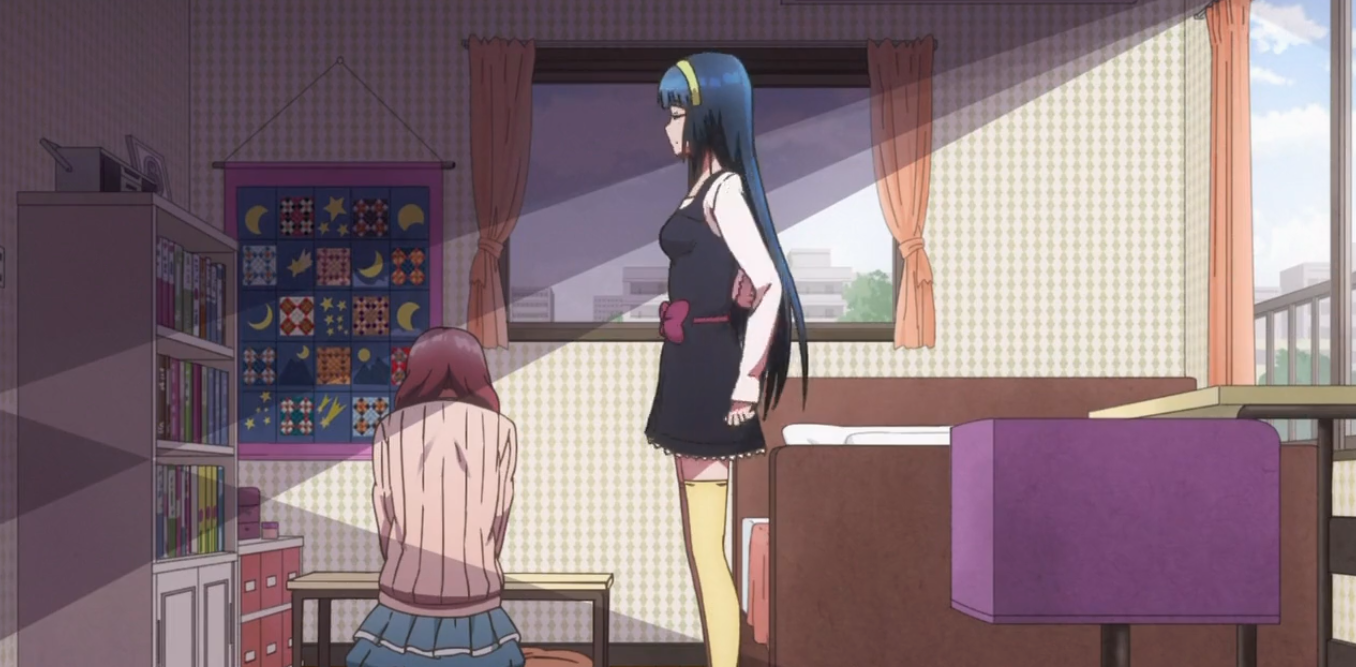

Hidamari Sketch (1-3) and Hidamari Sketch x 365 (4-6), ©Ume Aoki, Houbunsha / Hidamari Apartments Management Association

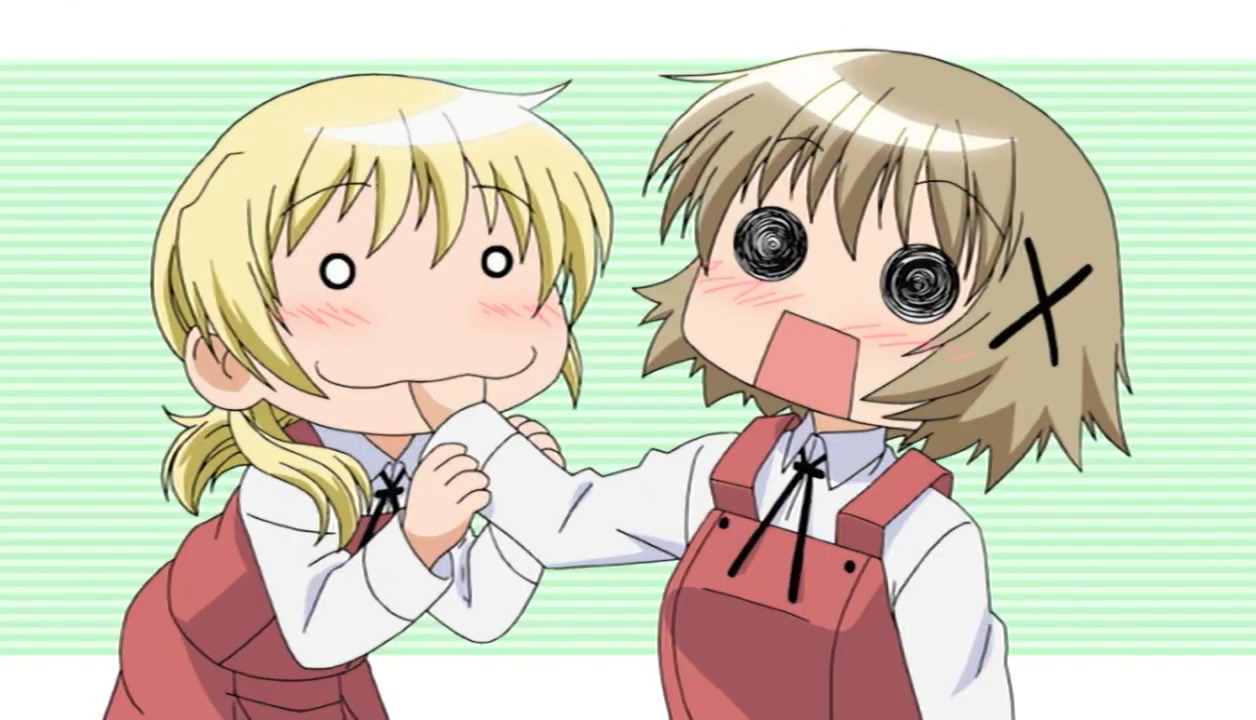

Hidamari Sketch's opening is cute, it's fun, has soft colors, real-life photography (see all of the art stationery), and generally the aesthetic of the show itself, with all of the background materials and patterns showing up. I think in the show's second season, which he was also the OP director for, his likeness for material patterns and more of his general coloring style comes out as they're used to texture the characters themselves, which I think is one of his more influential stylistic choices on other directors.

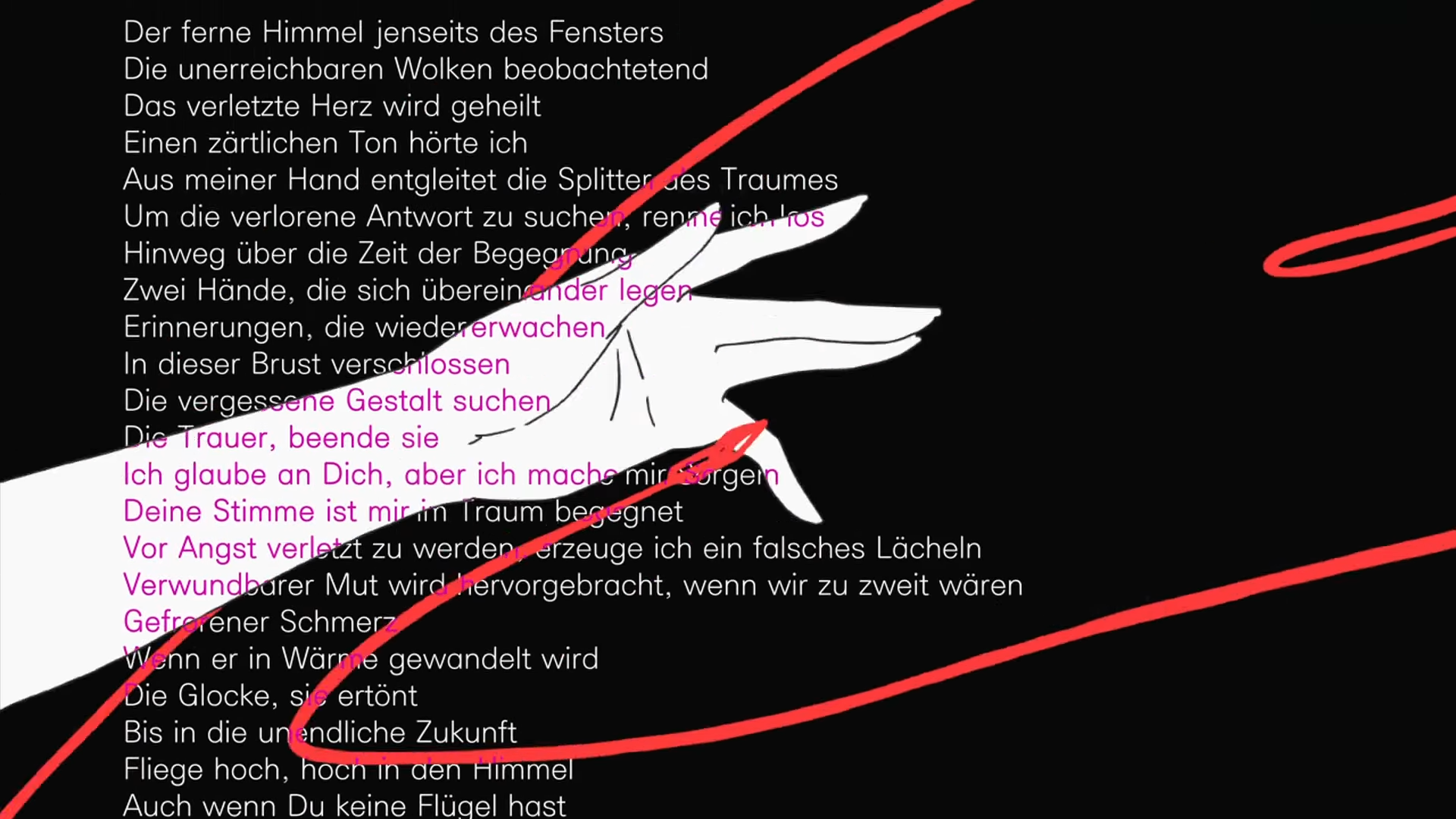

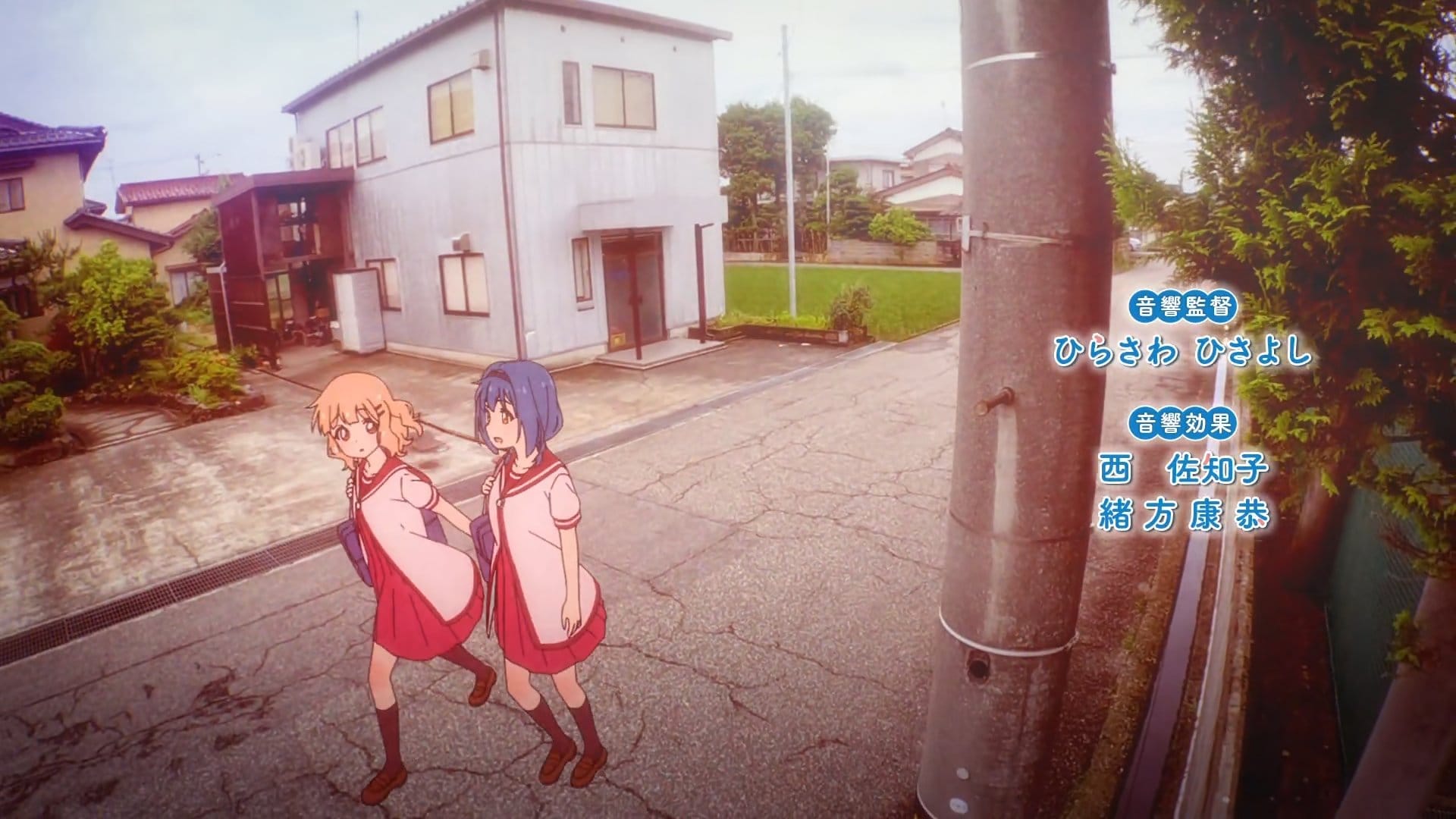

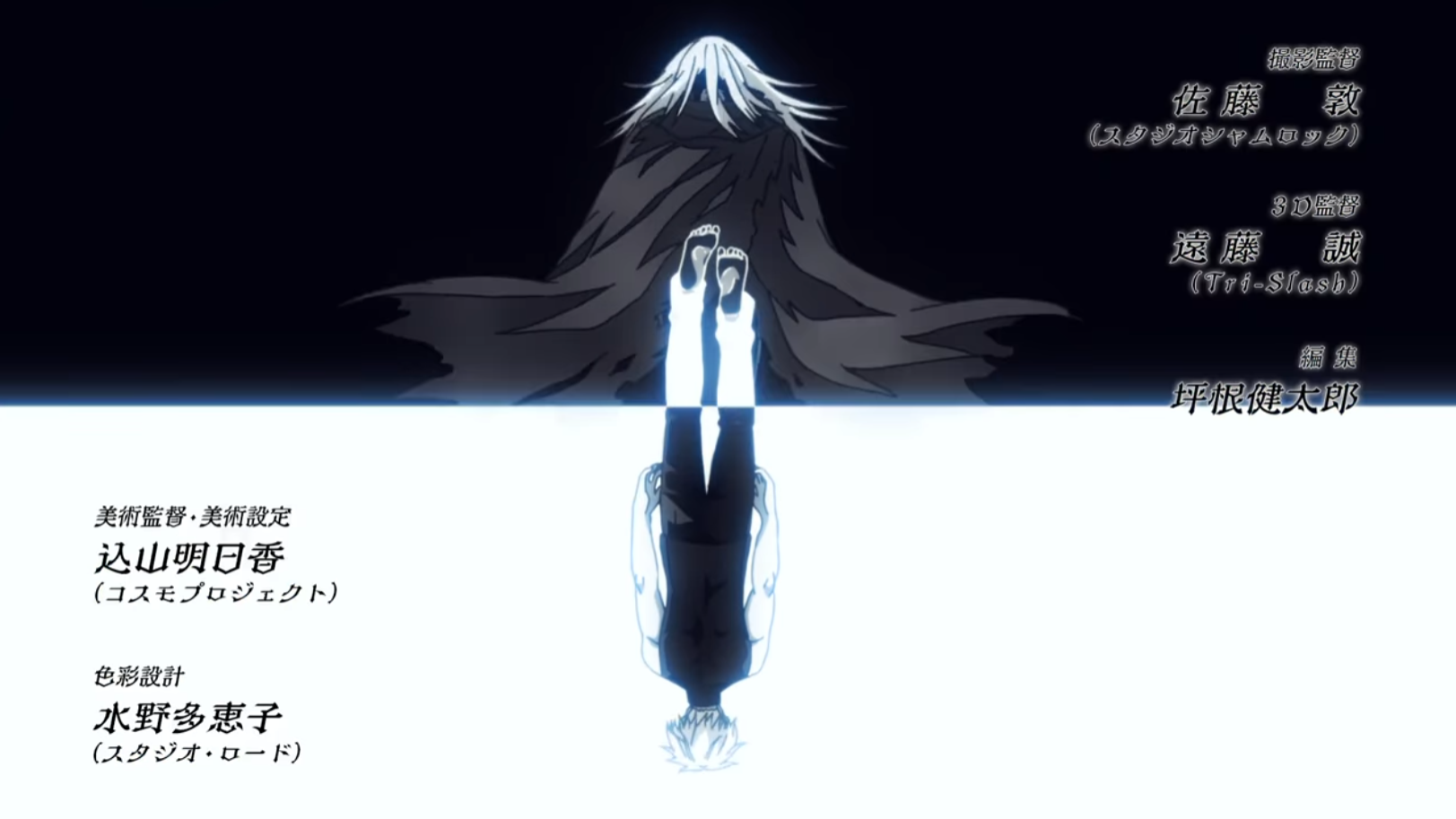

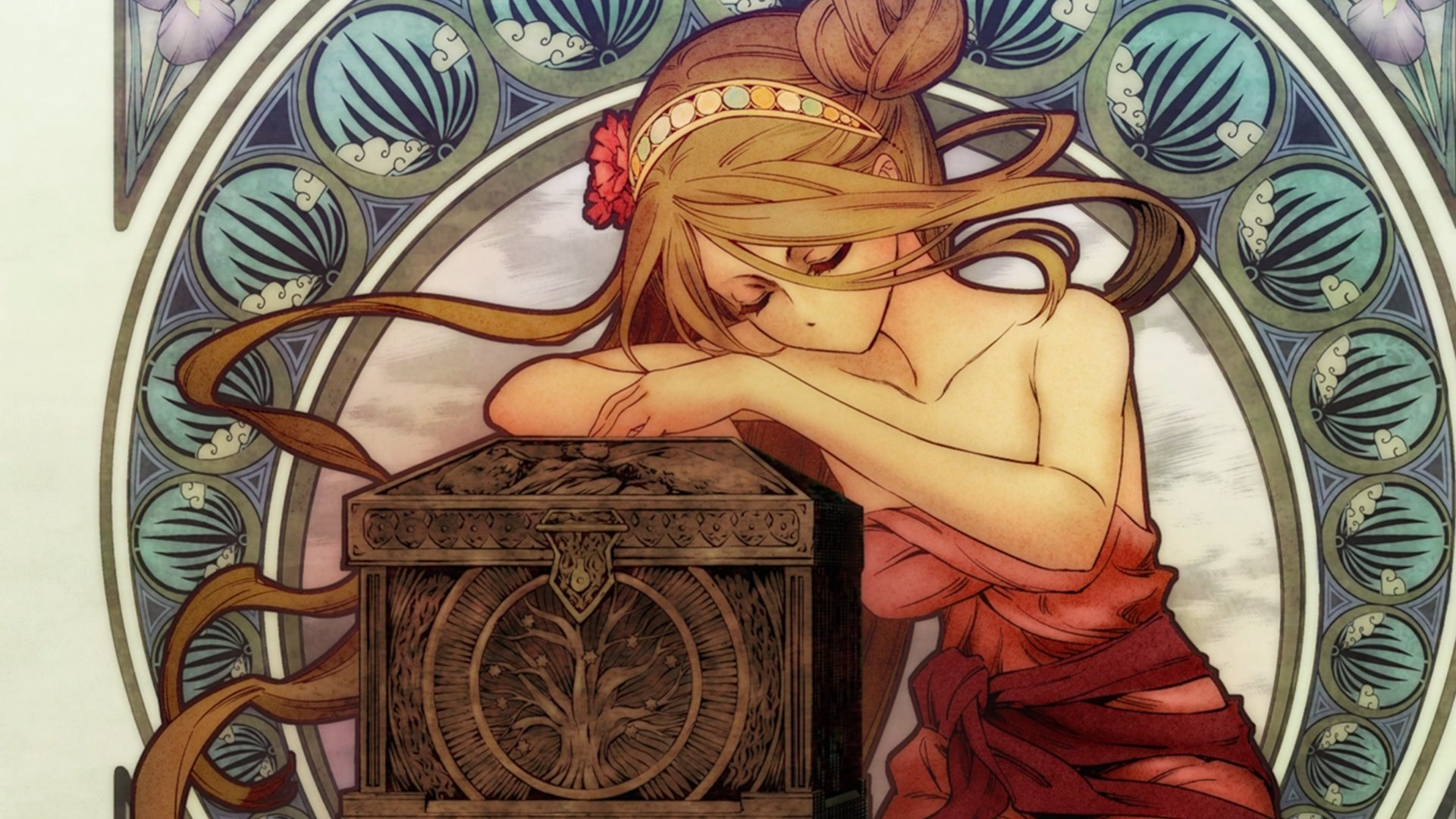

The crux of Oonuma's OPs at SHAFT are more popularly remembered through Ef, Natsu no Arashi, and an opening whose reputation precedes both the series it's from and the creators involved with it—Bakemonogatari's "Renai Circulation." Each of these openings is something completely different from the other in the stories that they tell and what exactly they're doing according to Oonuma's intentions.

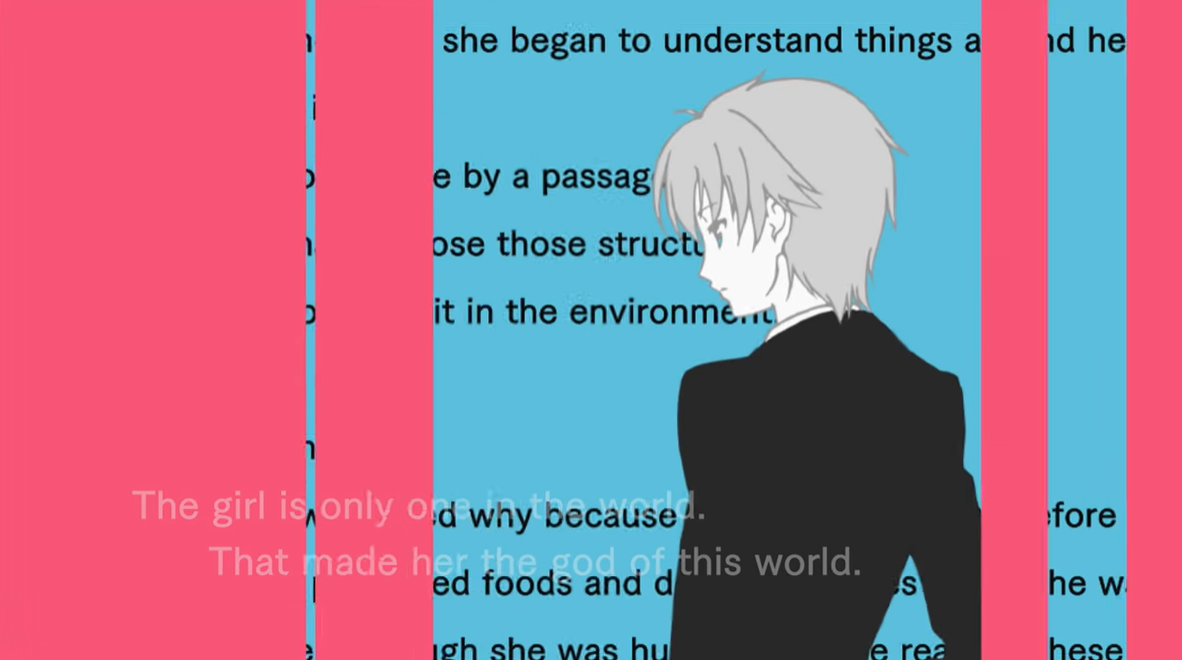

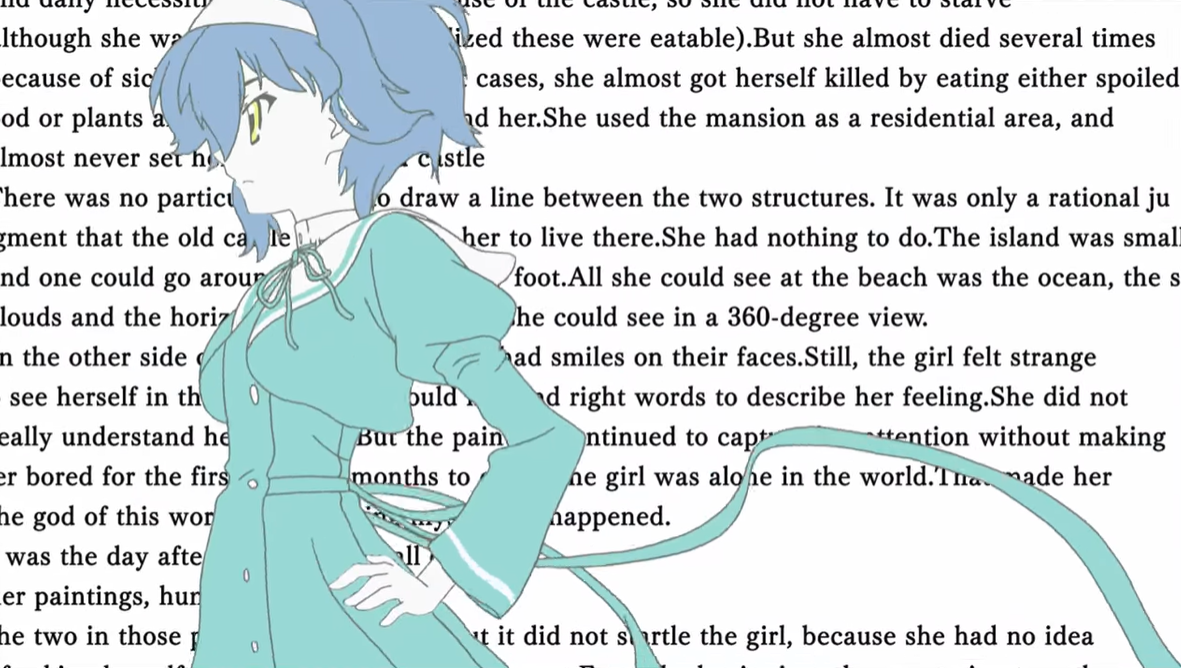

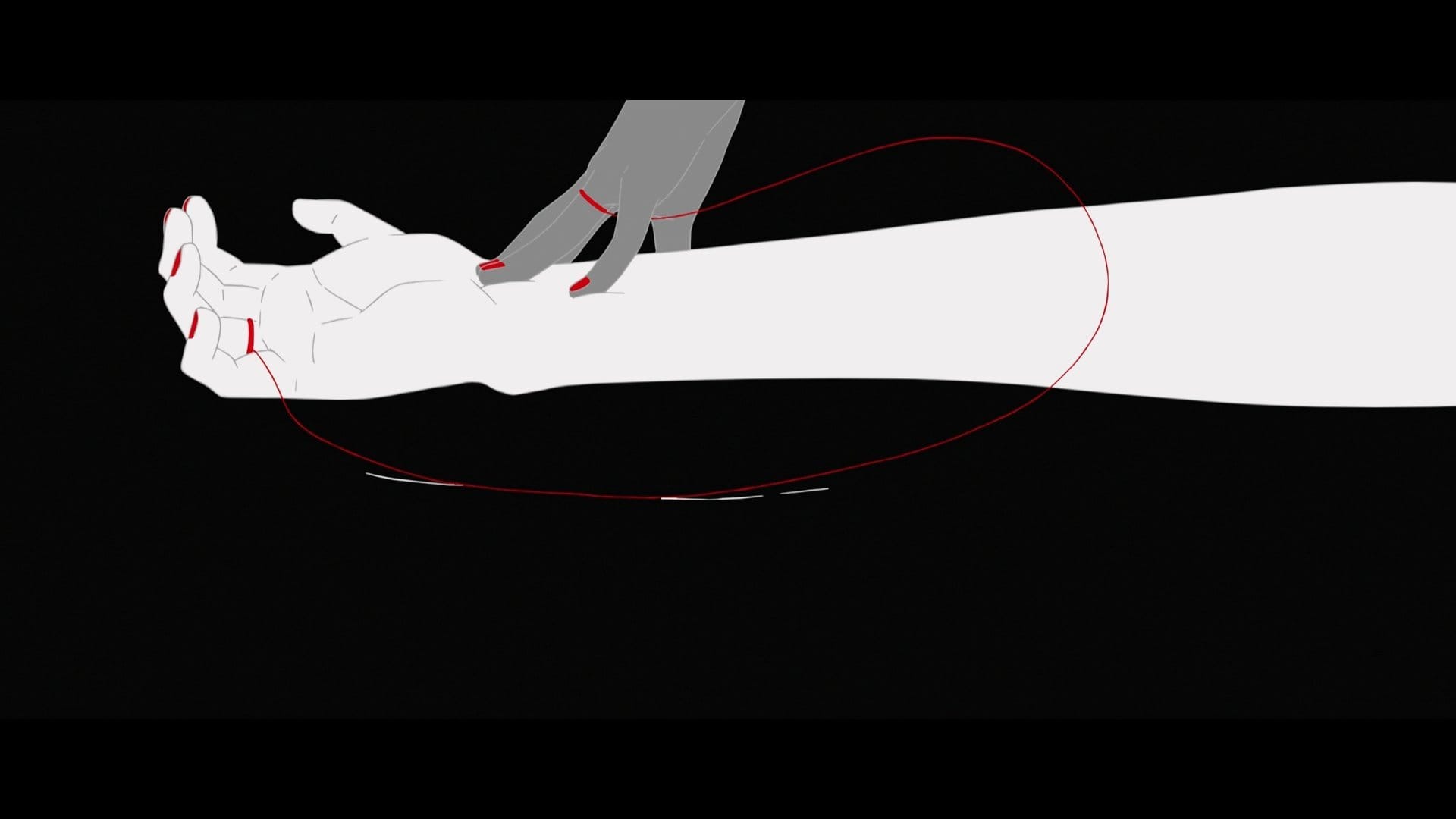

Ef: A Tale of Meloldies (1-3) and Ef: A Tale of Memories (4-5), ©Minori / Ef Production Committee

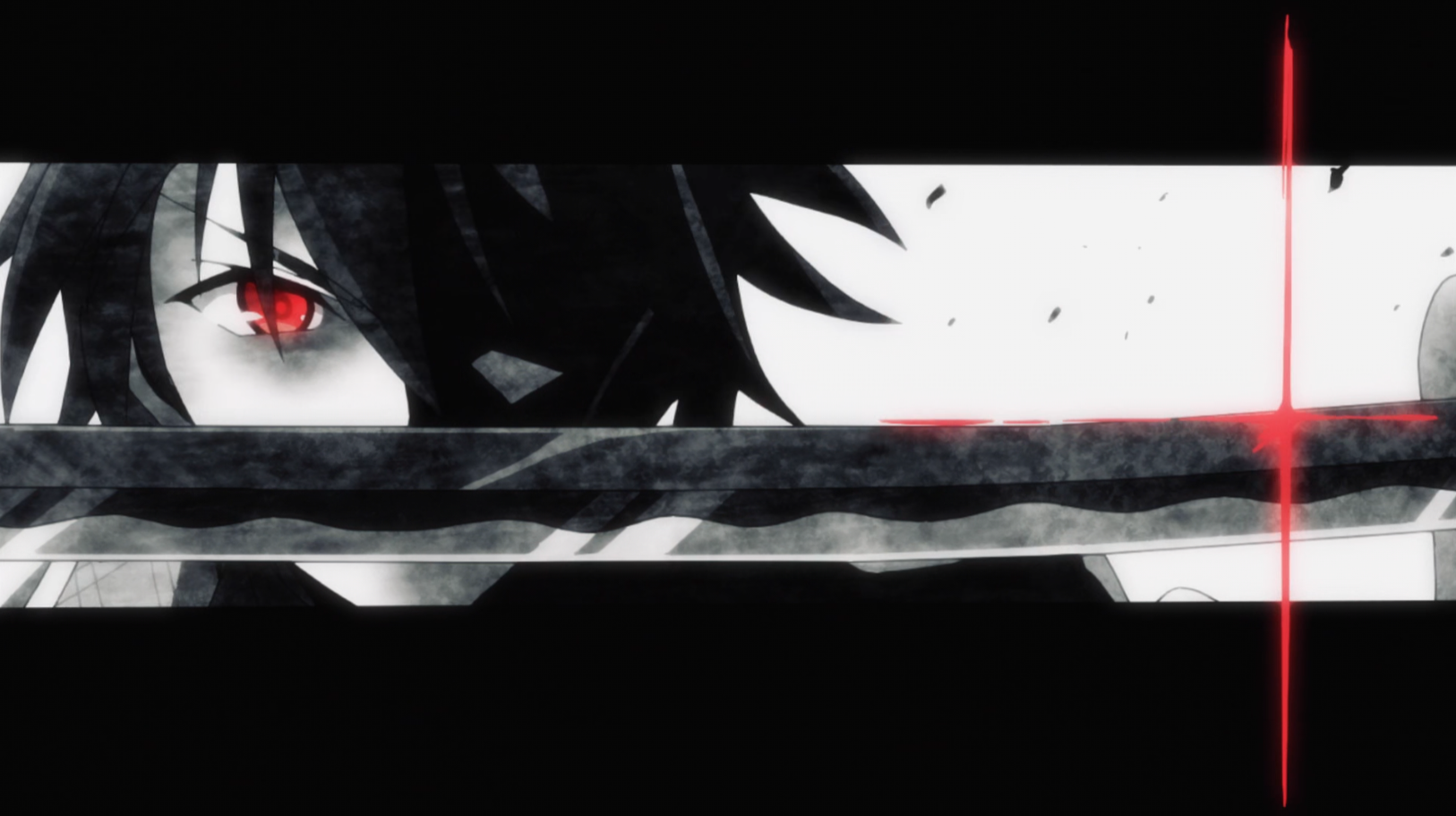

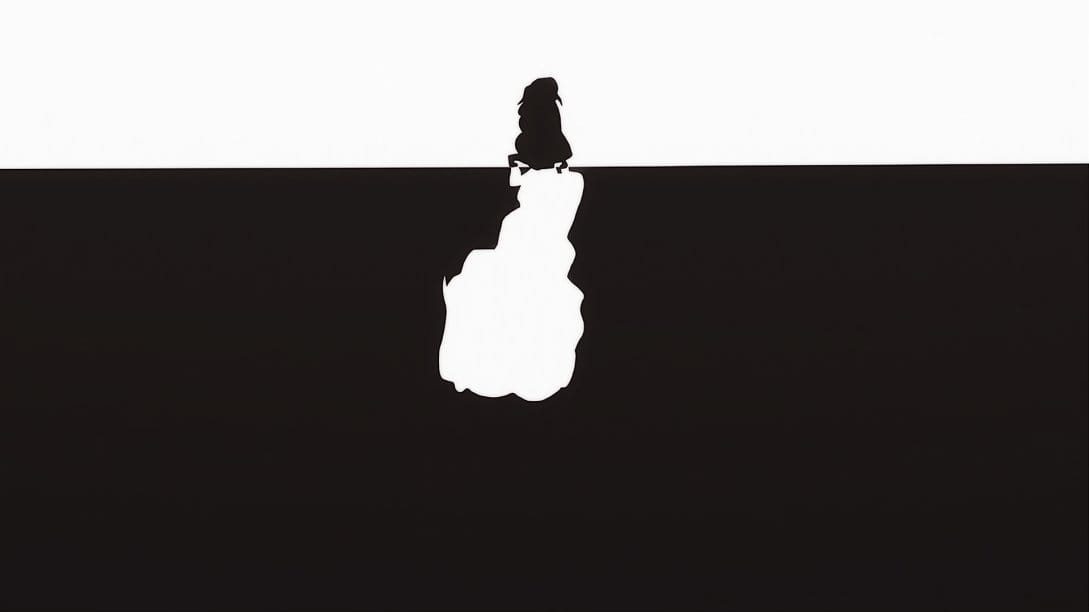

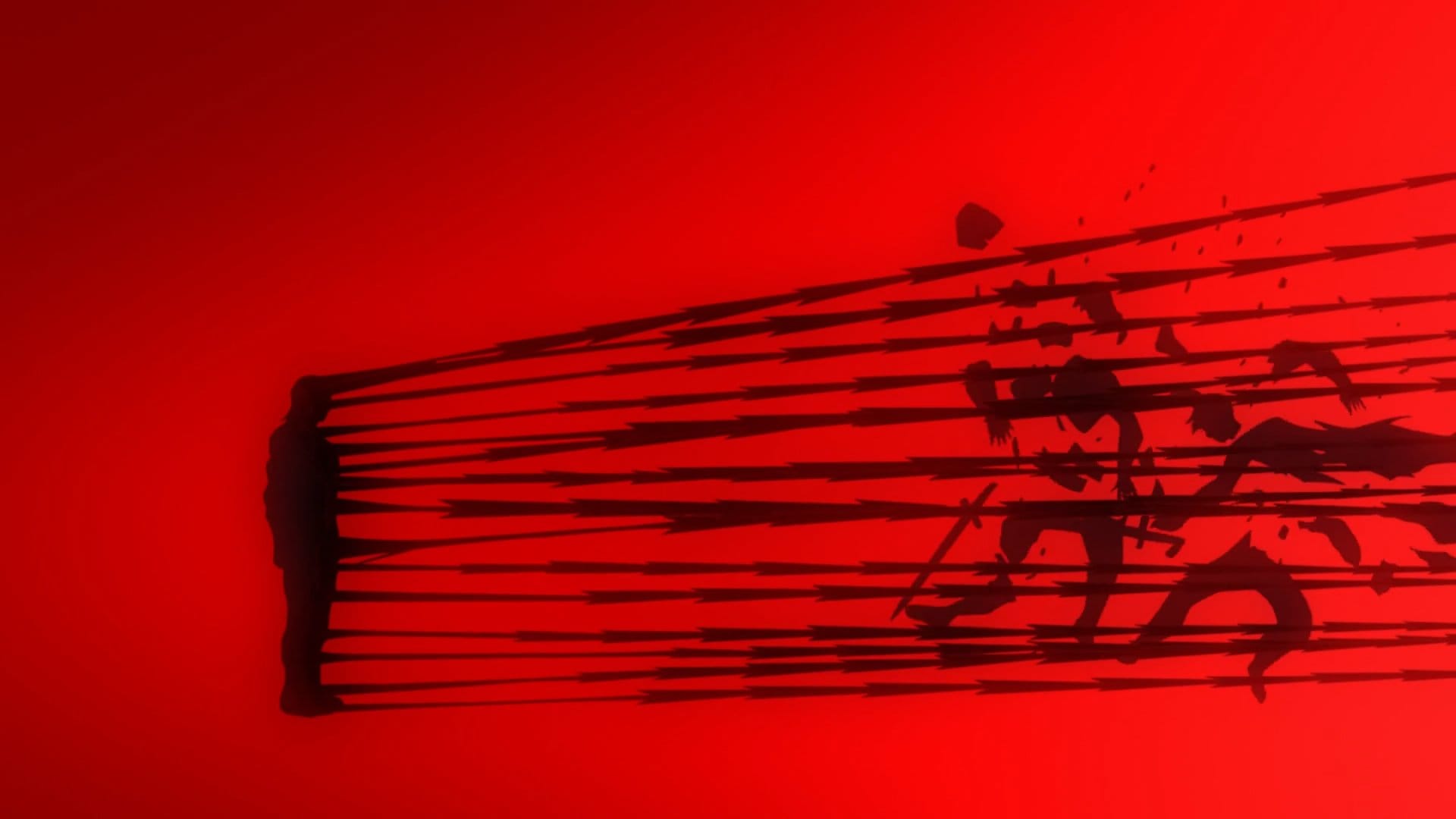

As a drama based on the various stories of various girls and those around them, Oonuma's Ef openings charge in with direct thematic motifs in mind. He uses text as part of the compositional framework, and most of this text is derived from the opening songs or other songs in the series that have been translated into English and German. Of secondary note is the same ideation in softness of colors, but these colors are again primarily contrasting and correlating with the negative space of whites and blacks on the screen rather than with each other. The brightness of the yellow in image two pops out against the white because of the ink pen's black segmentations and her framing within it as a reflection. While Oishi intends to lunge and capture the eye with his high-saturation, high-chroma color schemes popping off of the screen, Oonuma seems to lure you in.

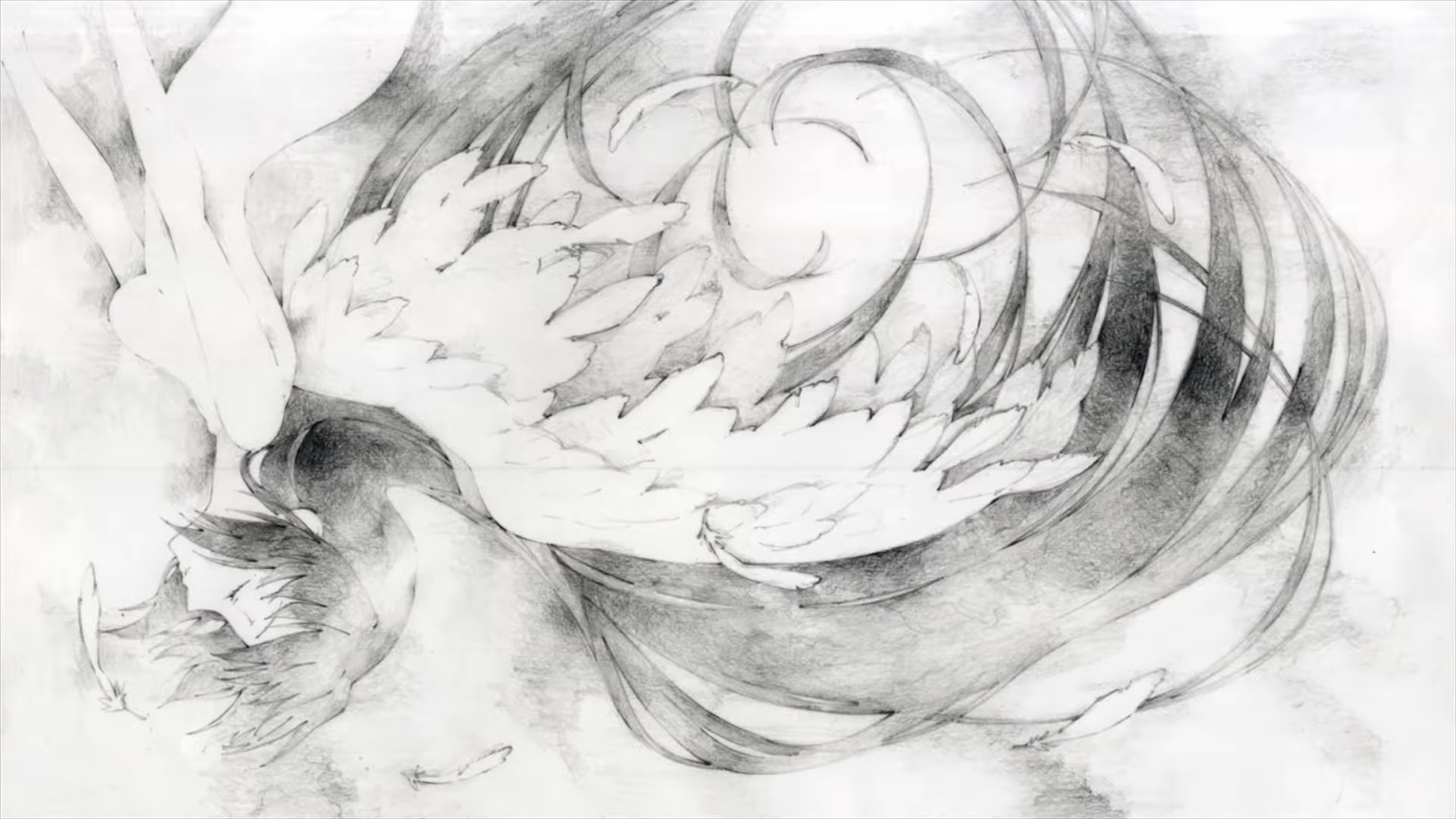

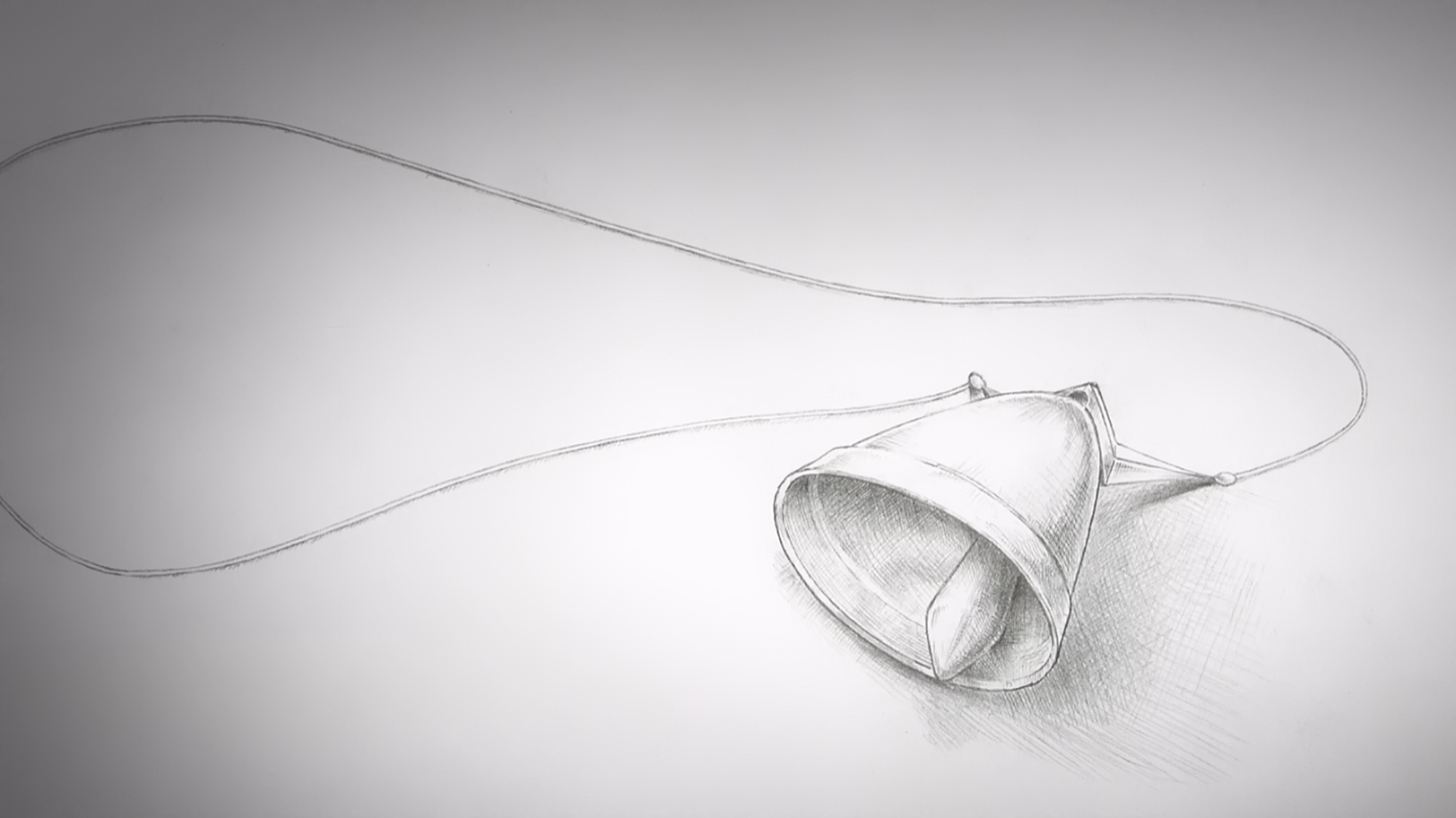

The first image in the above examples shows highly unconventional framing with lines of pink on top of a blue background as if to bar the viewer from observing the character. In animation, these bars actually morph and change sizes like they're mimicking rainfall. The bottom three images are from the second series, and a lack of color is present with the same stylistic tendencies. Shinbo liked to make small changes to openings and endings throughout the course of series' runs, and Oonuma does something similar here and in other shows. In Ef, new elements are unveiled, colors appear where black-and-white originally was, or figures that were entirely silhouetted are eventually "lit" and detailed. He also starts inserting cuts of graphite-looking drawings of the characters and important objects to bring specific focus to them as a general contrast to the rest of the OP's art styles.

Natsu no Arashi's first opening takes the idea of "reference" into a new realm of existence: every single posed 4:3 aspect ratio freeze frame in its entire 90 seconds is a reference to a completely different album cover, with the credits and title of the show inserted as all manner of typographic styles. There's a 15-year-old video on YouTube that covers every reference. I think it's fun that most of the cuts start out in standard 16:9, but the aspect ratio moves into 1:1 to look like an album cover. Oonuma things. The middle part that starts around the 30-second mark also changes to something different every episode, again always (or at least, most of the time?) being a reference to another album. The OP has different versions besides that, and in the linked example, the succeeding sequence has all of the nude, simplified figures of the girls colored in softer monochromatic colors, while in another episode, they're kept as silhouettes (also the poses are still album references).

Natsu no Arashi! (©Jin Kobayashi / King Records, Natsu no Arashi Production Committee); Bakemonogatari (©NisioIsin / Aniplex, Kodansha, SHAFT)

In Bakemonogatari, Oonuma approaches the aesthetic of Nadeko's opening with a softness between the background colors, shadow color, and foreground character colors; and Araragi's appearances, like in the first image, are given an overlayed monochromatic darkening that flattens his form as if he himself is just a shadow figure in both the literal appearance of the opening and in the context of Nadeko's adoration. Rather than using his shifting framing, Oonuma takes varying horizontal and vertical rectangles and instead transforms and scales them around the screen to lead the eye. A series like Monogatari works well in Oonuma's style considering he tends to focus on non-objective storytelling methods; and a show like this, where each character is shown only through perspectives of Araragi and themselves, which largely influences the world view and the unfolded events, plays into that idea, especially a character like Nadeko that puts up a facade in her behaviors and adoration of Araragi. The mix of the song and fluffy visuals feel like they contrast even though the general atmosphere is presented as "cute." It's great.

Natsu no Arashi and Bakemonogatari were Oonuma's last works with studio SHAFT as an internal part of the team. He directed not only the opening, but also one of the two episodes in this arc of Bakemonogatari. Natsu no Arashi, on the other hand, was his last project as series director under Shinbo. He directed its first season and then half of season 2, which was finished by Kenichi Ishikura. For some reason, Ishikura received no actual credit, and the "series director" role was left blank after episode 7, but SHAFT was kind enough to list Ishikura and Oonuma for the season together on their website.

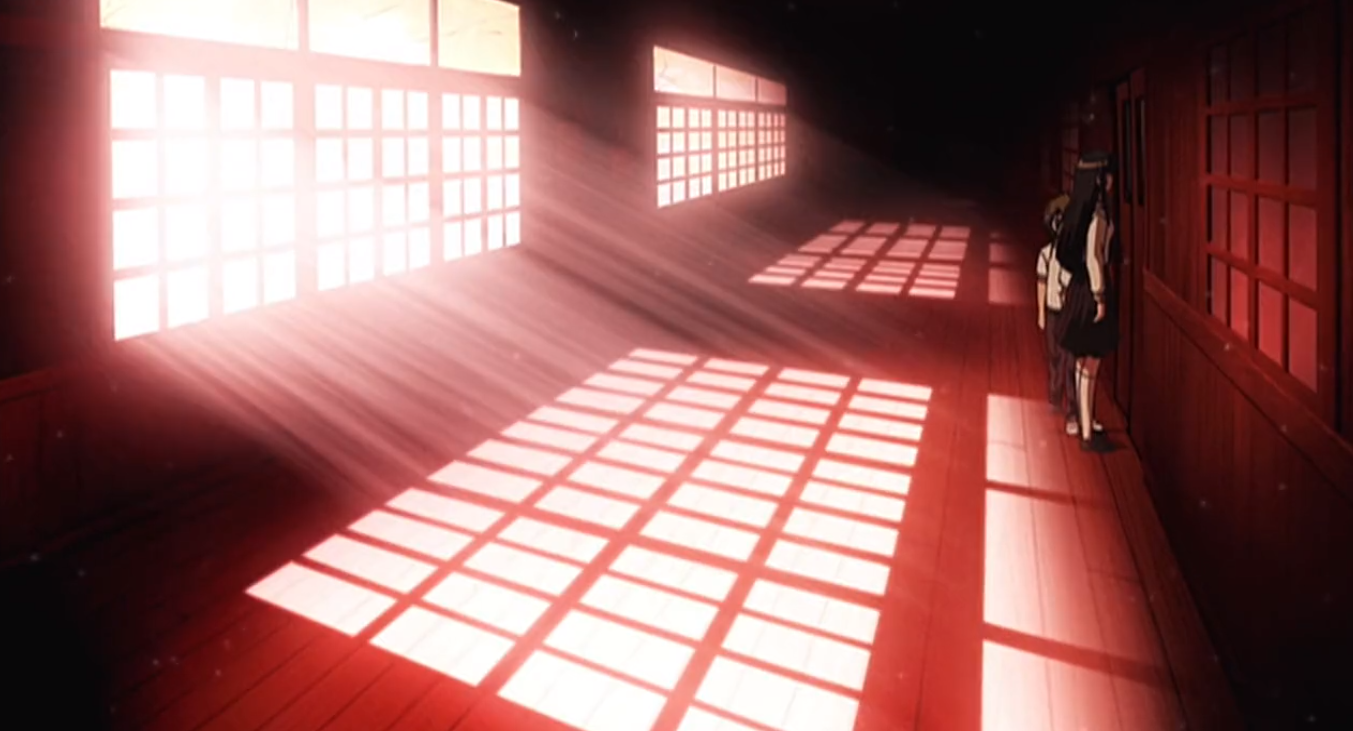

Natsu no Arashi is generally more of a comedy work with a dramatic setting. One part Shinbo and Oonuma kind-of co-influenced the rest of the studio with during this specific production is the use of hard-edge, shaped geometric lighting. Of course, Shinbo and other directors were already using shaped lighting on other productions, but Shinbo's idea for this series was that it was to emphasize "summer" and the heat of the summer and essentially use that style across the entire production. He employed a style of geometric lighting inspired by art director Yuuji Ikeda's work in the 1991 anime Marude Dameo, on which Shinbo was an episode director. From there, he asked Oonuma to figure out how to emphasize the hot atmosphere, which he certainly succeeded in doing so by having the photography team composite colors over the shape edges, increasing the brightness around them in the lit areas (or in outside scenes, increasing the brightness and contrast as a whole in the lit areas), and decreasing the brightness levels in the "unlit" areas.

Generally, other uses of this kind of a style by directors up until this point had a light sense of logic as to how the light was applied. The way the lighting was shaped wouldn't necessarily make sense, but it'd look cool and interacted with the mise-en-scène and characters in the mainground, and that was kind of the point: it's a compositional tool. In Natsu no Arashi's case, the idea is abstracted a little bit more. There's not really any mind paid attention to the background elements or anything like that. If you look at the third image below, the light shape is purely arbitrary besides the fact that it is cutting the screen in two and forcing the focus where they want the audience to pay attention.

Natsu no Arashi!, ©Jin Kobayashi / King Records, Natsu no Arashi Production Committee

The Oonuma Effect: SHAFT

Oonuma's influence on SHAFT itself is largely related to his aesthetic and processing choices. To this day, the pattern and color style he was most known for using is still sometimes employed by the directors or colorists of the studio. The geometric lighting of the 2000s SHAFT series is still strongly used on certain SHAFT productions by some directors, though whether or not that was more of a Shinbo-Oonuma influence or something else might be debatable

Although Oonuma was not specifically a mentor to anyone at the company in the same way that Shinbo was, the briefly mentioned directors Miyamoto and Tatsuwa are the closest to students that Oonuma had. While working on Negima!?, Oonuma was looking for episode directors, which led to Miyamoto joining the production having just left Vega Entertainment. Miyamoto worked and studied under Oonuma for about a year. Interestingly, Oonuma was described as Shinbo's right-hand man for the time he was at SHAFT essentially due to how many series he was given responsibility of and his understanding of what Shinbo wanted, and Miyamoto ended up in a similar position after Oonuma left SHAFT; though, Miyamoto's style in art design or visuality is not anywhere near as strong as Oonuma or Oishi since he's not a very individualistic creator.

Magia Record (©f4samurai / Magia Record Partners); Monogatari Series: Off & Monster Season (©NisioIsin / Aniplex, Kodansha, SHAFT)

Tatuswa, on the other hand, worked closely with Oonuma early on as a key animator and made his storyboarding debut on one of his series. Tatsuwa's desk during the production of Pani Poni was next to Oonuma's and character designer Kazuhiro Oota's, so he regularly got to see other animators' work and other material, which led to him developing an interest in directing. Tatsuwa's coloring style ended up being slightly closer to Oonuma's as far as the "softness" of the color contrasts, but maintaining otherwise unorthodox coloring direction.

Oomuro-ke: Dear Sisters & Dear Sisters (©Namori, Ichijinsha; Oomuro-ke Production Committee); Seitokai ni mo Ana wa Aru! CM (©Muchimaro, Kodansha / Aniplex)

Another director at least somewhat influenced by him is Tomoyuki Itamura (板村智幸). Itamura didn't work with Oonuma very much, but one of his first jobs at the company after moving there from OLM was as an assistant to an episode of Pani Poni. In more recent years, things like the trailer for Itamura's The Case Study of Vanitas evoke a similar style to Oonuma's morphing frames, which was humorously pointed out by Pilo on Twitter. Itamura's general color sense runs more along the lines of Shinbo and Oishi's, but he does occasionally evoke something slightly more Oonuma-like.

There also seems to be some homages made here and there. Naoya Nakayama (中山直哉), who otherwise has no connection to the studio, may have directly referenced Oonuma's work when he directed the first ED to Assault Lily Bouquet (2020), which has some striking resemblances to Oonuma’s Ef openings in color, composition, and theme.

Ef (©Minori / Ef Production Committee; screens 1 & 3) and Assault Lily Bouquet (©Azone International, Acus / Assault Lily Project; screens 2 & 4)

There's also an episode of Kyou no Go no Ni (2008) at studio XEBEC that the earlier-mentioned Kamitsubo was in charge of, which has a greyscale segment interrupted by hollow circles of soft, solid colors on a flat plane gradient; and I have to wonder if maybe that was just a little bit of an influence from Oonuma somehow...

Kyou no Go no Ni, ©Koharu Sakuraba, Kodansha / Kyou no Go no Ni Production Committee

There's also this weird case that... truthfully I don't know where to fit it in this article.Director Kousuke Murayama (村山公輔), who was employed by SHAFT as an animator from 2000-2003 but continues to operate with them as a freelancer occasionally, used Oonuma-like direction for a single series in 2016. Generally, Murayama is a strong artist with strong foundations, but his directorial debut, the hentai Resort Boin (2007), and subsequent hentai he directed didn't suggest anything of particular SHAFT influence. Somewhere along the way, he got a job as the director of Tawawa on Monday, which is one of the more uniquely SHAFT-looking non-SHAFT productions, but only because it evokes Oonuma specifically

The reason I say that is because it actually feels a lot more like Oonuma's work at SILVER LINK, but to my knowledge Murayama has never worked with Oonuma while he has been at SILVER LINK. The overlapping color multiply filters framing some shots, material pattern backgrounds, undetailed characters, silhouettes, and the vibe of the color choices seem to be inspired by Oonuma and potentially even a little bit of Kamitsubo (save for the very last screenshot in the collection below, which is more Shinbo-like, please see Nurse Me or The SoulTaker for further reference). Murayama hasn't approached a series in this way since then, despite having "modern SHAFT" directing sensibilities (modern meaning post-2018) in his recent productions like Grisaia: Phantom Trigger (2025).

Tawawa on Monday, ©Kisekihimura / PBM

Early SILVER LINK Era (2009-2013)

SILVER LINK was founded at the end of 2007 by Hayato Kaneko (金子逸人), a former producer from animation studio Frontline. Kaneko was nearing his 30s, and Frontline was mainly a sub-contracting studio, rather than a primary production studio taking on series. Kaneko wanted to produce series, so after speaking with the president of Frontline, he went independent as SILVER LINK and brought along some Frontline-associated staff, including animators, production assistants, and directors. After about a year of mainly doing gross outsources, including to SHAFT on Ef and Bakemonogatari, the studio produced their first series, Tayutama: Kiss on My Deity, with director Keitarou Motonaga.

Oonuma was invited to the company as he and Kaneko knew each other before SHAFT (Mizuiro, Oonuma's first work as director, was outsourced to Frontline; but even earlier than that, Oonuma was a key animator on various Frontline-Kaneko involved episodes in the late 1990s and early 2000s). The general story seems to be that Kaneko wanted a director to establish SILVER LINK, similar to how SHAFT's Kubota looked to Shinbo to establish something new at SHAFT, and Oonuma was to be a chief director of SILVER LINK.

Oonuma’s workflow is a bit similar to Shinbo’s to a degree. Shinbo’s work can be best described as a supervising, overlord-like existence at SHAFT. While he isn’t responsible for Bakemonogatari’s on-site directing or French New Wave aesthetics (that was all Oishi), he is responsible for many of the show's decisions, both in general aesthetics (think about the similarities between every Monogatari adaptation) and storytelling, as well as organizational direction. Likewise, Yukihiro Miyamoto is Madoka Magica's "series director," but Shinbo didn't get the Newtype Award or Tokyo Anime Award for "Best Director" on the show for nothing (and people like Masahiro Mukai don't consider him to be a mentor-like figure for nothing).

Shinbo also doesn’t storyboard or direct many episodes himself, instead leaving that up to the plethora of episode directors or storyboard artists that come in (though he occasionally does draw storyboards under a pseudonym). Shinbo focuses on using what the staff have made and revising or editing the content at that stage. Oonuma works on a lot of series like Shinbo in that he leans on the rest of the staff and lets them exist, but he’s not as reserved with his own participation. For many of the series that he’s involved with as a director, Oonuma will storyboard or direct at least one episode and the opening/ending. There are only a few rare instances where Oonuma is "only" credited as the director or chief director.

Oonuma's role as a supervisory director at SILVER LINK was probably never a tangible goal, considering the studio's near-instantly huge output. Just over half (6/10, including OVA series) of the company's works from 2010-2012 featured Oonuma serving as director or chief director, and it would clearly be too much for him to work on more than that consistently as the years went on and SILVER LINK continued to expand its production count. The most important director to SILVER LINK outside of Oonuma's general sphere of influence during this time is Shinya Kawatsura, who is a freelance director who has shown up on SILVER LINK productions since 2012. Kawatsura is actually the only consistent recurring "outside" director at "SILVER LINK proper." The term "SILVER LINK proper" is mainly to separate from CONNECT, SILVER LINK's subsidiary entity that has its own consistent group of directors.

For the purpose of simplifying the eras, most mentions of Oonuma's works in the SILVER LINK era will only briefly detail some series and there'll be more of a focus on Oonuma's openings and endings. There are simply too many to go into for one, and for two, we'll get to that.

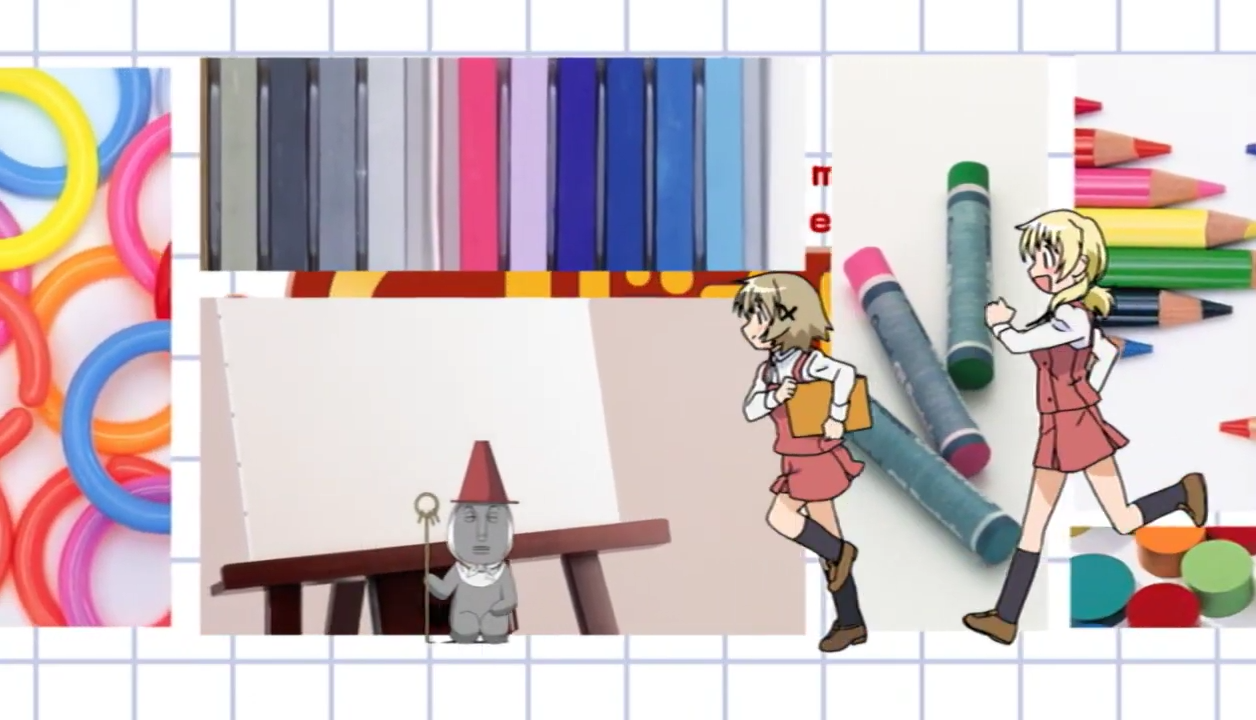

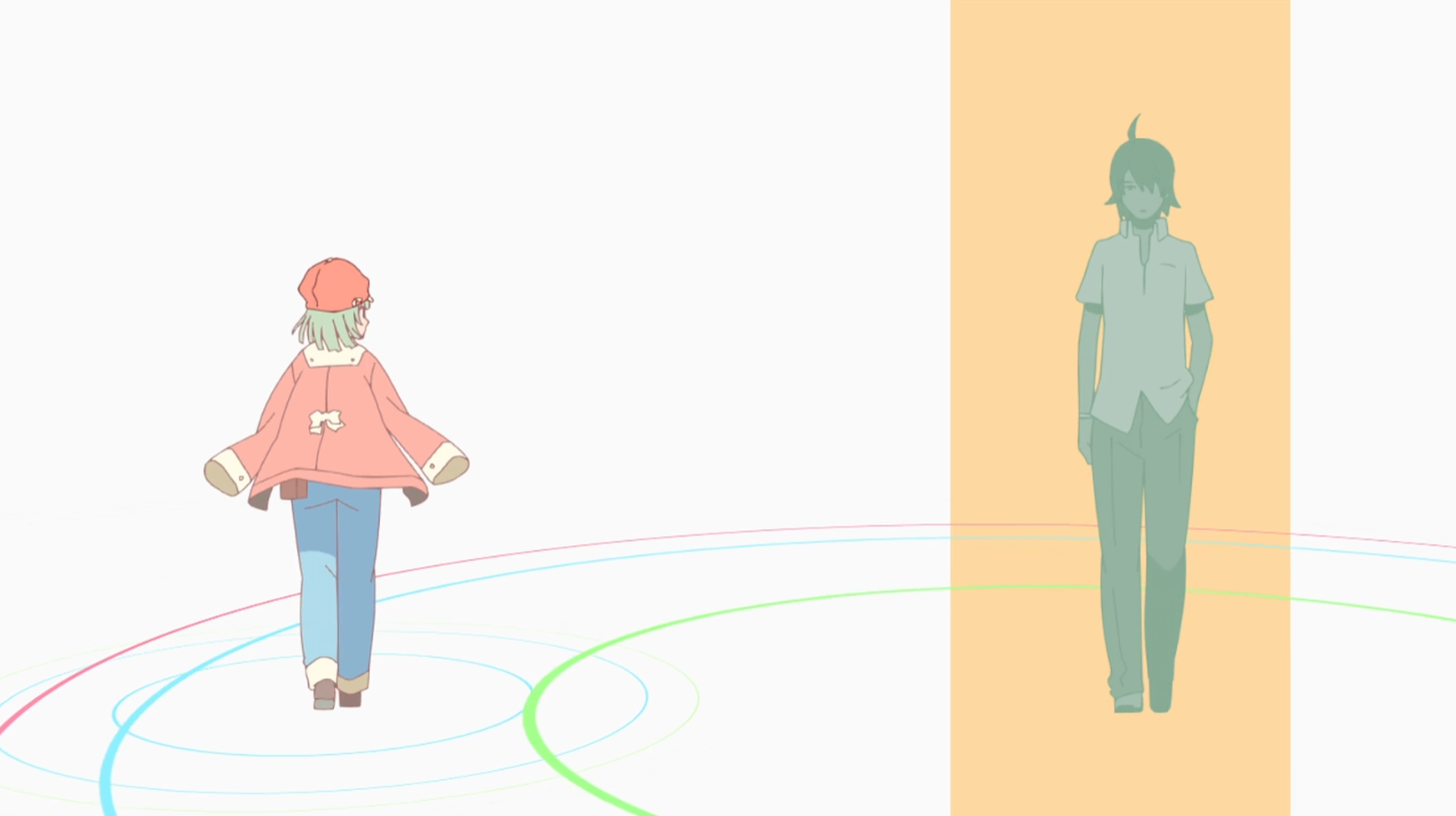

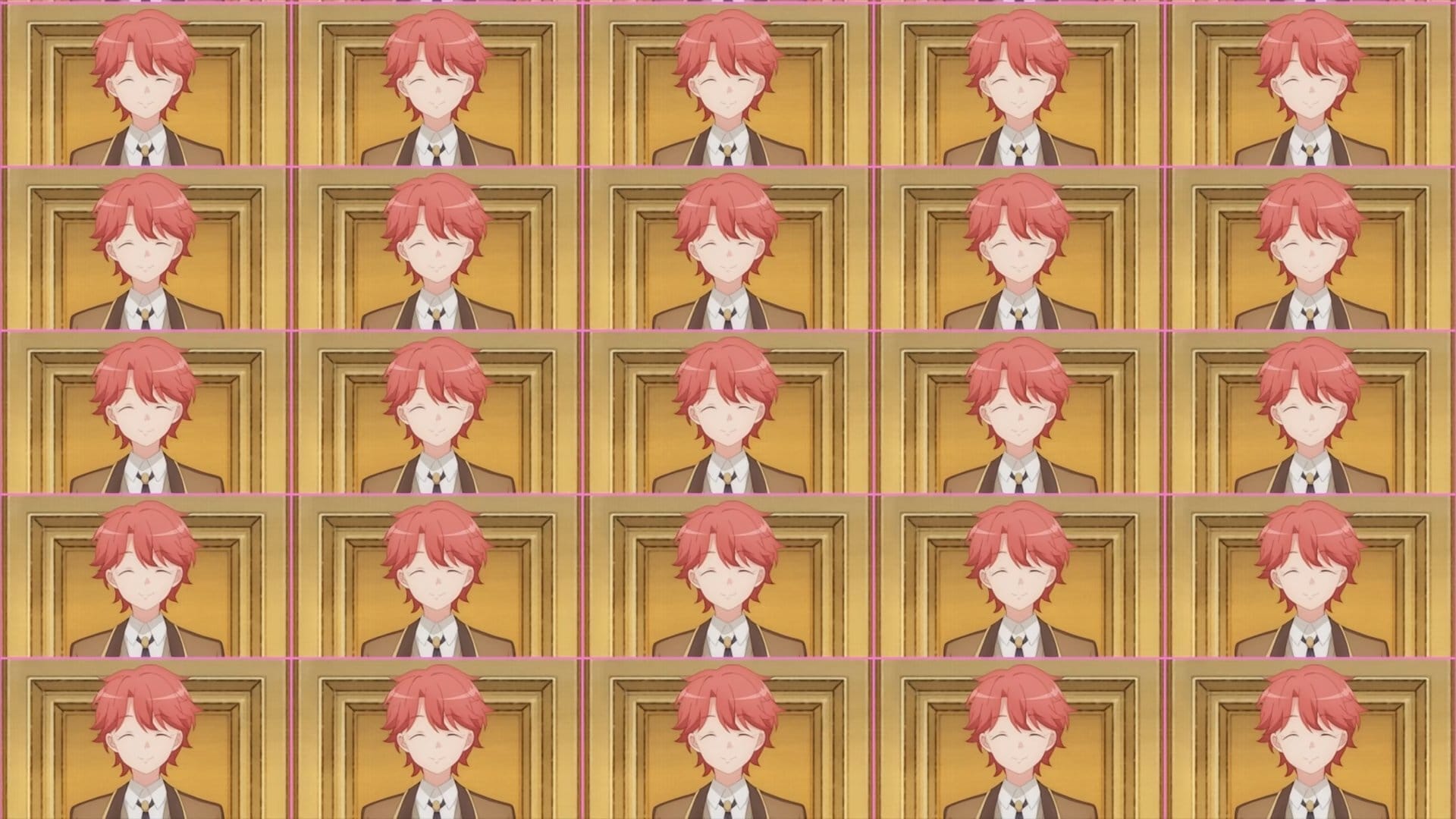

Oonuma’s first work at SILVER LINK was Baka and Test in 2010. One does not have to look much further than its first opening to see Oonuma clearly in action: the characters turning their heads, reusing the same pieces of animation, but giving each new cloned figure a separate paint job, is a relatively simple technique in showing off the characters. It looks nice, it's effective for its purpose, and it doesn't need a lot of time and resources to do. Leaving the section of patterns and shifting color scales, the OP shows a series of drawings of the characters staying in-tune with a bit of that monochromatic color filtering, and the hair of each character fades into white as it drifts across the screen. These same techniques continue throughout the opening, and what you have is a memorable but otherwise "easy to make" opening.

Baka and Test, ©2010 Kenji Inoue / Kadokawa Corporation Enterbrain, Baka and Test Production Committee

The first episode has a similar approach to Oonuma's other works. The opening narration has images of characters in seats, all patterned and featuring soft color designs, with each character’s cels moving individually for a parallax effect. Then Oonuma uses actual parallax as the camera moves from right to left around a teacher observing students with some students passing in front of the camera. The editing is quick, and the shaped geometric lighting is there. It gives a distinct manga-like aesthetic that’s fitting for the series. Osamu Dezaki-esque cuts and harmony frames are used for fun gags, and the show generally follows these looks. The show also had an important Oonuma connection from his SHAFT days–series composition writer Katsuhiko Takayama (高山カツヒコ), who was the head writer for both Ef and Natsu no Arashi, and also an episode writer as far back as Pani Poni Dash!

Baka and Test, ©2010 Kenji Inoue / Kadokawa Corporation Enterbrain, Baka and Test Production Committee

To immediately contrast with Baka and Test, Oonuma’s second series at the studio was C3: Cube x Cursed x Curious. C3 has its comedic elements and is part of the late 2000s-early 2010s moe fad, in this case as a harem, but it's a drama with action and supernatural powers, and not as much of a gag comedy set in a school. Rather than looking at mostly singular images and reaching for minimalistic and cost-cutting design, C3 is faster with its editing and cutting, and is an action series. Some reviewers and fans early on pointed out Oonuma's origins as a SHAFT director through this series in particular because of the similarity in cut tempo.

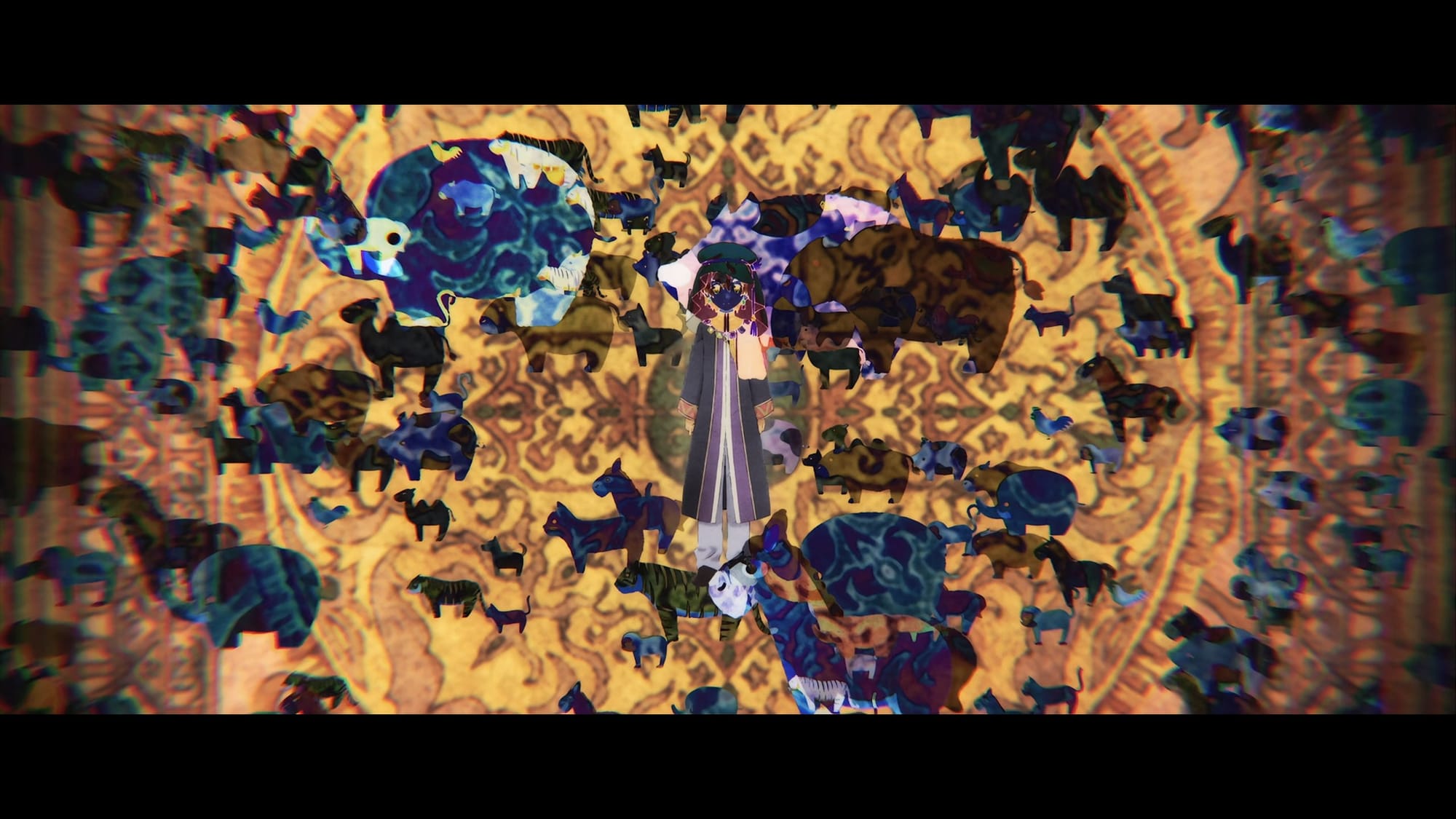

It's a rare one-cour series that also has two different openings, each directed by Oonuma. The first opening is nice and has some cool transitions between the characters, such as a tree moving past the camera like a screen wipe. In the second opening, Oonuma frames the first segment of the screen vertically with a blue highlight going down the center of the screen and the sides of the frame fading into black while there are interjectory medium- and close-cuts going around the character's faces and bodies. Following the title, there are shots of blue-tone characters standing in the background in a stylized cinematic aspect ratio (the "black bars" are patterned) with a foreground character popping out in a complementary orange-tone color overlay.

In between each of the cinematic character shots, there are splices of close-ups of the orange-toned characters' faces and quick cuts to moving, patterned wagasa umbrellas against similarly patterned floors/backgrounds in a bird's eye view. Afterwards, there is a montage of the characters using a single camera angle, expositing their personalities a bit, and quick-cuts of singular drawings done in black-and-monochrome composite coloring, and a rather elaborate animated sequence of fight cuts. It’s a different side of Oonuma’s directing that even his works at SHAFT didn't touch on much, since his only series that had considerable action was Negima!?.

C3: Cube x Cursed x Curious, ©Hazuki Minase / ASCII Media Works, C3 Production Committee

Oonuma’s next work was Dusk Maiden of Amnesia, the only other Oonuma work at SILVER LINK in which Takayama has served as main writer. This was Oonuma’s first time directing with a series director under him, again in a similar vein to Shinbo's role at SHAFT. In this case, it’s Takashi Sakamoto (坂本隆), who is confirmed via storyboards from the series to be a pseudonym used by ex-Studio Pastoral member Shuuji Miyazaki (宮崎修治), who was participating with SILVER LINK under the Sakamoto name since 2011 with Baka and Test 2. Miyazaki is an important part of the 2011-2013 years for two reasons: even though he didn't stick with Oonuma for long, he's the first series director to work under Oonuma; and he's also, at the time, ex-SHAFT talent. As mentioned, Miyazaki previously worked for Studio Pastoral, and Pastoral was SHAFT's most trusted outsourcing company from around 2004 to 2011. Miyazaki was one of the Studio Pastoral staff members entrusted with directing and storyboarding (and on the SHAFT series, even for episodes that Studio Pastoral weren't responsible for producing), and therefore his sensibilities as a director is the closest director to Oonuma's stylistic sensibilities at SILVER LINK for that time.

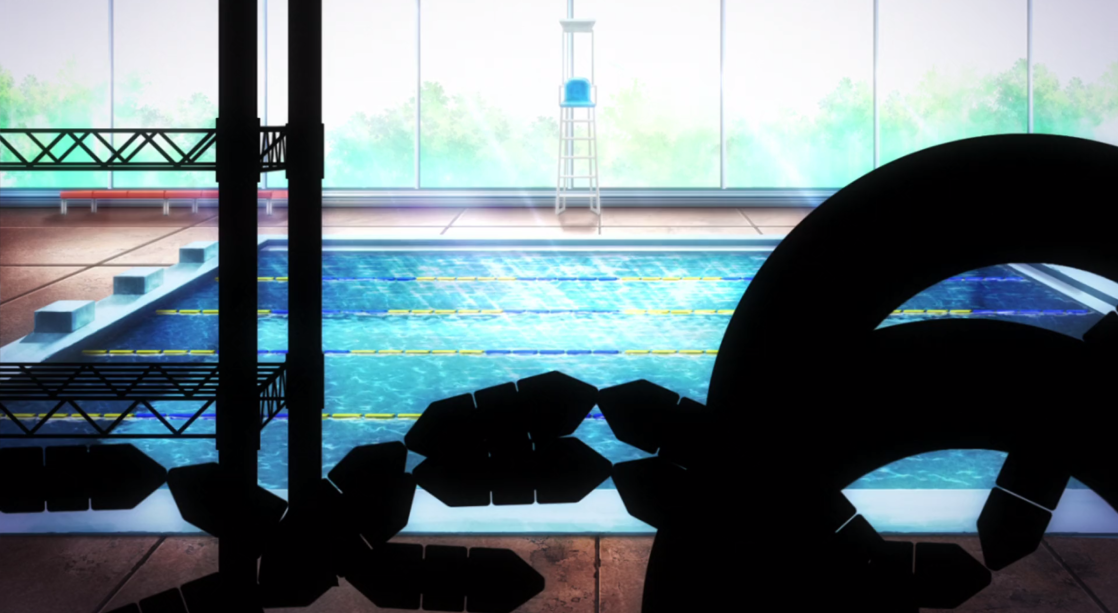

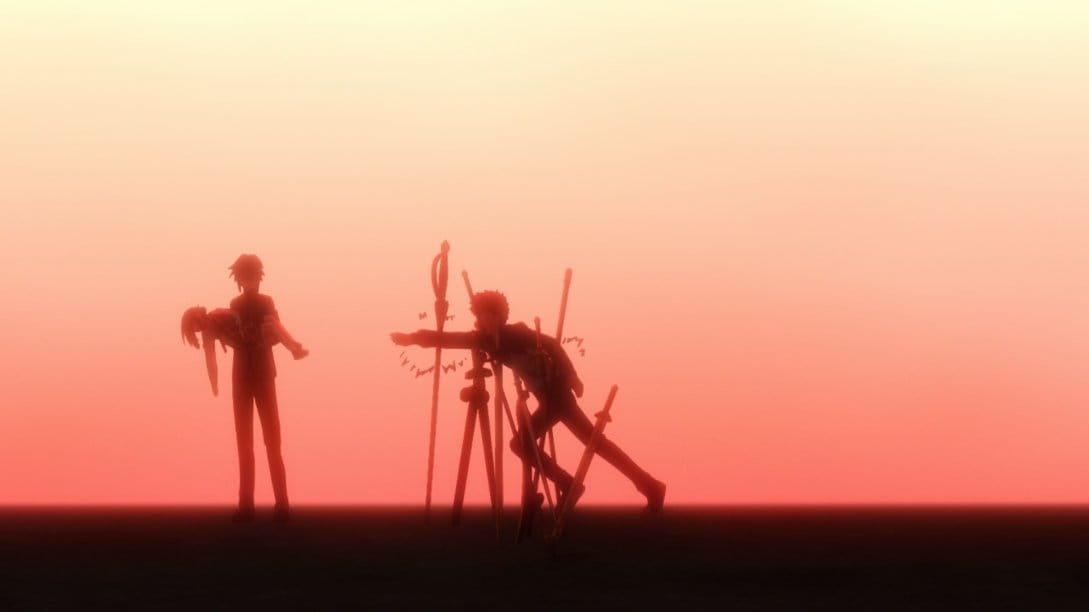

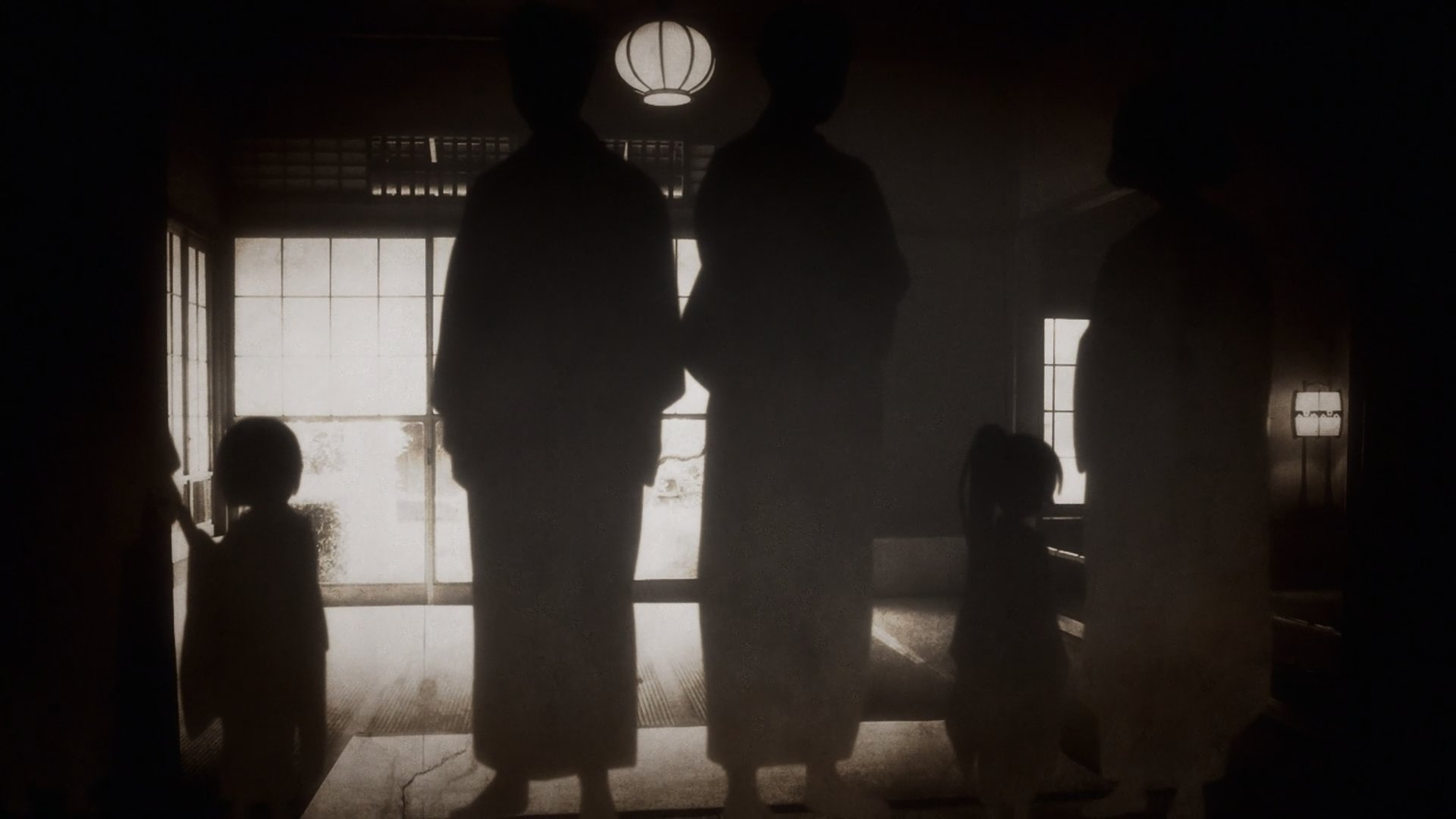

Among all of the Oonuma-SILVER LINK works, Dusk Maiden stands out from the rest. His and Miyazaki's touch across the series is undeniable. Weird vertical aspect ratios and framing, completely silhouetted objects, wide-shot compositions using shadows to lead the eye, fish-eye-esque lenses, shifts into other aspect ratios, intense foreground layout elements, and so forth. Dusk Maiden also, of the SILVER LINK works, feels like the closest to something that would have been adapted by Oonuma’s former studio–it takes up a similar space as Natsu no Arashi in a series focused on an adolescent boy who develops a friendship with a ghost girl. It also has the backdrop elements of wartime Japan like Natsu no Arashi, somewhat coincidentally, but none of these comments are to disservice Dusk Maiden: it and Natsu no Arashi are different takes on a similar idea.

Dusk Maiden of Amnesia, ©Maybe / Square Enix, Dusk Maiden of Amnesia Production Committee

I’ve seen friends and others say that Dusk Maiden is the last series that feels truly "Oonuma-like" because of the drastic shift from his "usual" style to something much more, as I would put it, complacent. It was after Dusk Maiden that Oonuma tried his hand at being in a supervising position in a capacity like Shinbo, which only truly lasted for some series up until around 2018.

At the beginning of this change for Oonuma is Kokoro Connect, in which he acted as chief director with Kawatsura directing. It feels far more like a Kawatsura project given Oonuma’s likely loose supervision across the series... which is to be expected, but Oonuma has no credits on the series besides his "chief director" role. He wasn't in charge of any episodes and didn't have anything to do with the OPs. I don't know how involved he was in the work, but I see him participating at the pre-production meetings, going over the screenplay, and overlooking the storyboards, but otherwise giving Kawatsura control (which would also include Kawatsura overseeing the storyboards).

Oonuma also took on the Fate/Kaleid series as its chief director. At first, he had Miyazaki (Sakamoto) and Mirai Minato (another pseudonymous director, whose identity is... we'll get to that) as series directors under him. For Fate/Kaleid's television run (2013-2016), Oonuma mostly sat back doing his chief direction duties rather laxly. He was the co-storyboard artist for the first episode, and boarded/directed two of the DVD specials for the fourth season (3rei), but otherwise gave control to the other staff. Masato Jinbou (神保昌登), one of Fate/Kaleid's series directors, reminisced in an Akiba Souken interview that Oonuma wasn’t strict on how he directed his seasons of the show and gave a great degree of freedom to the series directors. It’s safe to assume, based on Fate/Kaleid and Kokoro Connect, that Oonuma’s role as a “chief director” is similar to Shinbo’s method with Oonuma likely setting broad parameters to stay within the confines of, but otherwise just letting the directors do what they wanted.

Most likely either by request of Shinbo, Itamura (who took over as series director of Monogatari from Oishi), or studio president Kubota, Oonuma appeared one last time at SHAFT in 2013 when he directed the opening for the Otorimonogatari arc of Monogatari Series Second Season, which is basically a sequel to "Renai Circulation." Even though he had been out of the studio's sphere by around 4 years at that point, the opening feels right at home with its predecessor with instantly identifiable traits and the inherent, extreme subjectivity that persists with Nadeko's character in her first two arcs.

Monogatari Series Second Season, ©NisioIsin / Aniplex, Kodansha, SHAFT

SILVER LINK Modernus (2014-present)

The second era of SILVER LINK sees the company in its final years of independence with Kaneko as the company's CEO and its since acquisition by the Asahi Group and ABC Animation. The last truly "old-style" Oonuma series marks the beginning of this era, WataMote. It’s not the same style as Dusk Maiden, but Oonuma clearly directs the series using his tastes. Oonuma was in charge of the first episode, and derivatives of the previous techniques can be seen throughout. A constant in the series (and something more broadly influencing some of the SILVER LINK directors for a few of their works) is the use of geometrically shaped lighting and prominent light flares that take the shape of primarily pentagons and hexagons. The series also uses a variety of wide angles, color schemes scene-by-scene or even shot-by-shot, various shifts in art styles, and negative space framing.

WataMote, ©Niko Tanigawa / Square Enix, "WataMote" Production Committee

Oonuma's interpretation of WataMote rides a common line of comedy with elements of drama and genuine, expressive artistic moments (including all of the cringe that WataMote is known for) that make many of his previous works feel special and unique to his directing style. If anything, WataMote's later arcs might even be more in tune with Oonuma than what season one covered (see the OVA as an example). Series after WataMote certainly have Oonuma-isms, but they lack much of his specific individuality and the way he approaches themes in the source material. There's a tug-and-pull in a show like WataMote where a character tries to be moe, popular, or anything that will give her attention; as well as a very real human drama having to do with social anxiety, otaku culture, and trying to build friendships or overcome disliked aspects of the self purely from the biased perspective of its protagonist (reminds you a bit of Nadeko, doesn't it?).

So, what is the reason for the lack of Oonuma’s previous style in his works moving into the 'modern' era, then?

The answer is simple. Oishi and Oonuma described each other in a perfect way back in a 2008 roundtable discussion between 'Team Shinbo': Oishi is a “creator”, and Oonuma is a “businessman.” In other words, Oishi is more of an "auteur" creating things for the sake of his own self-indulgence and wanting to show the audience something different and surprising ("auteur" theory is generally pretty annoying to discuss in most conversations, though, so treat this phrase as a manner of speaking). Oishi isn't ignoring others' ideas or even putting himself on a pedestal, but rather seeking out the specific ideas and visions that he has while still keeping in mind what the fans want and the opinions of his colleagues. Oonuma, on the other hand, is much more focused on what he thinks the audience and authors of the material he adapts are thinking, and with that in mind, Oonuma is trying to appeal more to the audience than his own stylistic individuality. He said that he started to adopt styles he liked in Pani Poni, and part of the appeal of SHAFT was that they made weird, interesting, and at times avant garde works–in other words, Oonuma was able to play the role of the "businessman-type" by being a "creator-type." When he first moved to SILVER LINK, this held true: part of the appeal in being brought to SILVER LINK was to showcase his individualistic senses and give the studio a name, which clearly worked.

As time went on, SILVER LINK produced a lot more series, and Oonuma didn't have the time to keep up with all of the demand and probably wasn't expected to, which I think changed the way he approached the bussinessman model, alongside the kinds of works that he was now adapting. He’s still a businessman, but he thinks about the audience expectations and the author first and foremost; and SILVER LINK isn't a studio that prioritizes specific kinds of works or the staff's individual sensibilities in the same way. The studio doesn't have the same reputation of SHAFT, a "directing company", so even its name brand appeal is inherently different. That's why No-Rin, Invaders of the Rokujouma, and Anne-Happy include many of Oonuma’s tendencies, and clearly have his heart in them, but never delve fully into his style, especially when he isn't the sole director like in Rokujouma. As the relationship between Oonuma and his works changed, so did his organizational approach. For example, he was the director of A Sister's All You Need with Jin Tamamura (玉村仁) as the "series director," and Oonuma stated that he mainly directed up until around the storyboarding stage (pre-production), and then Tamamura basically took over for the production stage.

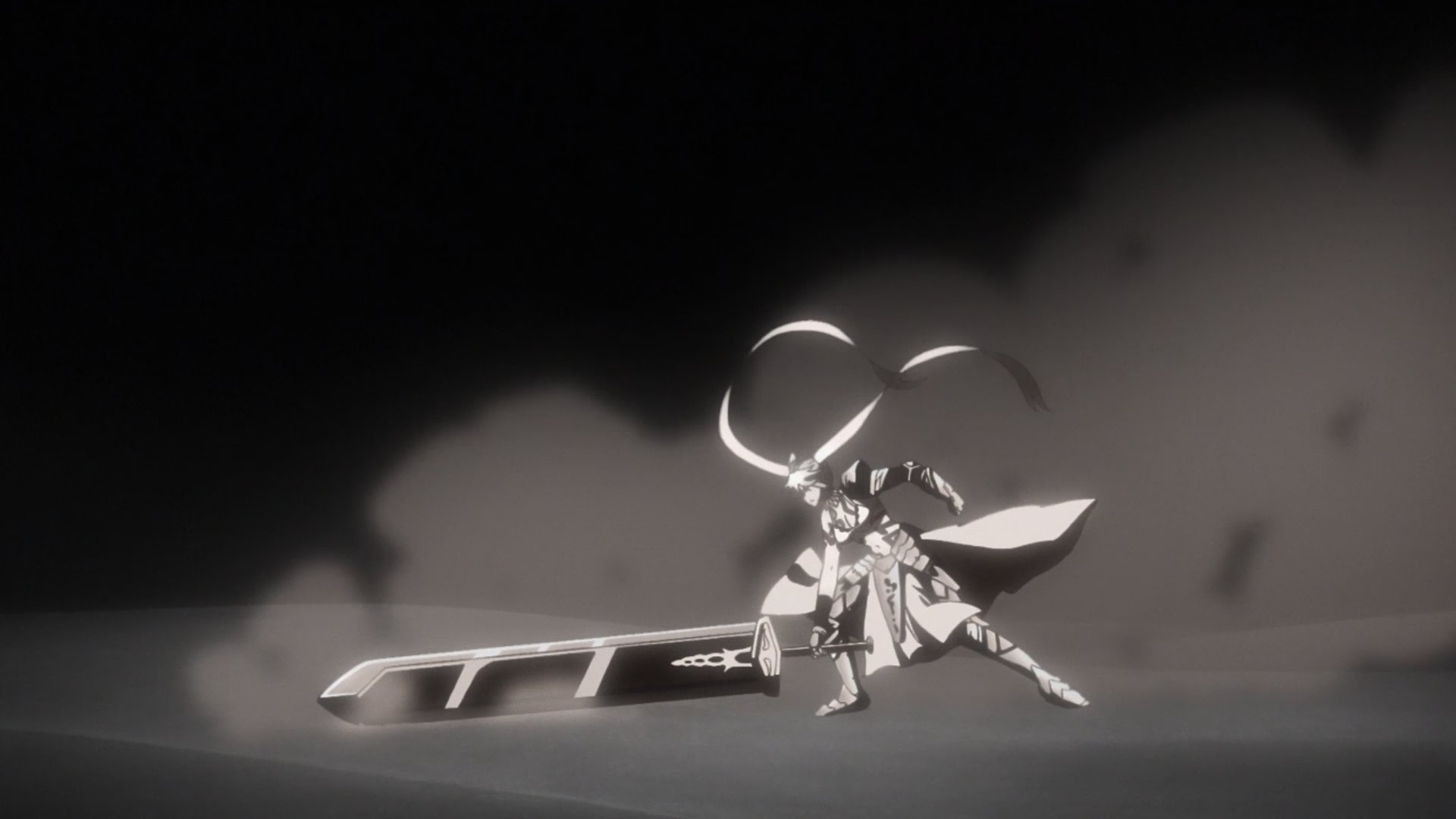

Part of being a "businessman" in any industry is selling a product and getting people interested in it–and what better way to get someone interested in a work than through a cool opening or ending theme? They're like gateways into different worlds, and the continuation of Oonuma’s experimentalism is specifically found in the openings he directs. Varying quality of the series aside, works like WataMote, The Misfit of Demon King Academy (2020), and Deep Insanity: The Lost Child (2021) accentuate Oonuma’s continued playfulness and curiosity. A common color scheme he’s come to use since (at least) WataMote is red and blue, especially for the linework or in monochromatic contrasts. Similar imagery from the days of Ef, with people bound by chains, make their occasional appearances too. Bofuri season 2's opening (2023) even has a reference to one of the Negima!? OVAs from nearly two decades earlier. Basically, he's kept his artistic personality as a constant, prominent feature of his work in this way.

Stills from openings of WataMote (©Niko Tanigawa / Square Enix, "WataMote" Production Committee), Chivalry of a Failed Knight (©Riku Misora, SB Creative / Chivlary of a Failed Knight Production Committee), The Ones Within (©Osora, Kadokawa / The Ones Within Production Committee), The Misfit of Demon King Academy (©Shu, Kadokawa Corporation / Demon King Academy), Deep Insanity: The Lost Child (©Etorouji Shiono / Square Enix), and The Misfit of Demon King Academy II Part 2 (©Shu, Kadokawa Corporation / Demon King Academy)

I think an issue with his modern output is that SILVER LINK, and by extension Oonuma, choose to adapt a lot of works that feel largely unsuited for him. On a subjective analysis, part of what makes series like Deep Insanity unsuccessful as a product is bad marketing from Square Enix, a story that moved too slowly and was simply not interesting enough, and the fact that it's a mixed-media project that did not have a concrete foundation. Most of Oonuma’s other recent adaptations are light novel fantasies, isekais, and MMORPG-based stories; and these stories aren't inherently a bad mix with him more so how it presumably affects his business-type approach. Some of these do work out pretty well, but it feels like they don't mesh in a quasi-rhetorical triangle of the material, the "author" (Oonuma & co.), and the audience. They're not works that play to Oonuma's strengths, nor necessarily to the kinds of works that he likes; and without decent production values, these aspects are made more apparent.

SILVER LINK has an issue with poor scheduling patterns without the staff to back it up: too many projects at once and not enough staff to allocate to all of them resulting in heavy subcontracting (Ragna Crimson), heavy outsourcing (Sasaki and Peeps is basically a co-production, BLADE produced half of the episodes), and some generally poor work from the different departments (distracting 3D and surface model texturing issues, poor animation supervision, poor layouts, etc.) that have to be done with tumultuous schedules. In 2023, the studio produced around 6-cours (72 episodes) and a feature film worth of content, including one series co-produced with BLADE (not including the CONNECT subsidiary's works, by the way).

Despite the issues that come with these overzealous overproduction problems, "Oonuma Cinema" is alive. Even though he only storyboards and directs (as an episode director) 1-2 episodes a year, it's not like Oonuma has lost his touch when it comes to processing complex scenes or plainly doing cool stuff. In Chivalry of a Failed Knight (2015) episode 3, Oonuma storyboarded and directed (with a rookie episode director) an awesome highlight of which isn't focused on pretty screen designs or thematic resonance like has been the basis of my particular fondness for his style thus far; but instead, an ambitious fight scene with skillfully processed 2D animation using a 3D background.

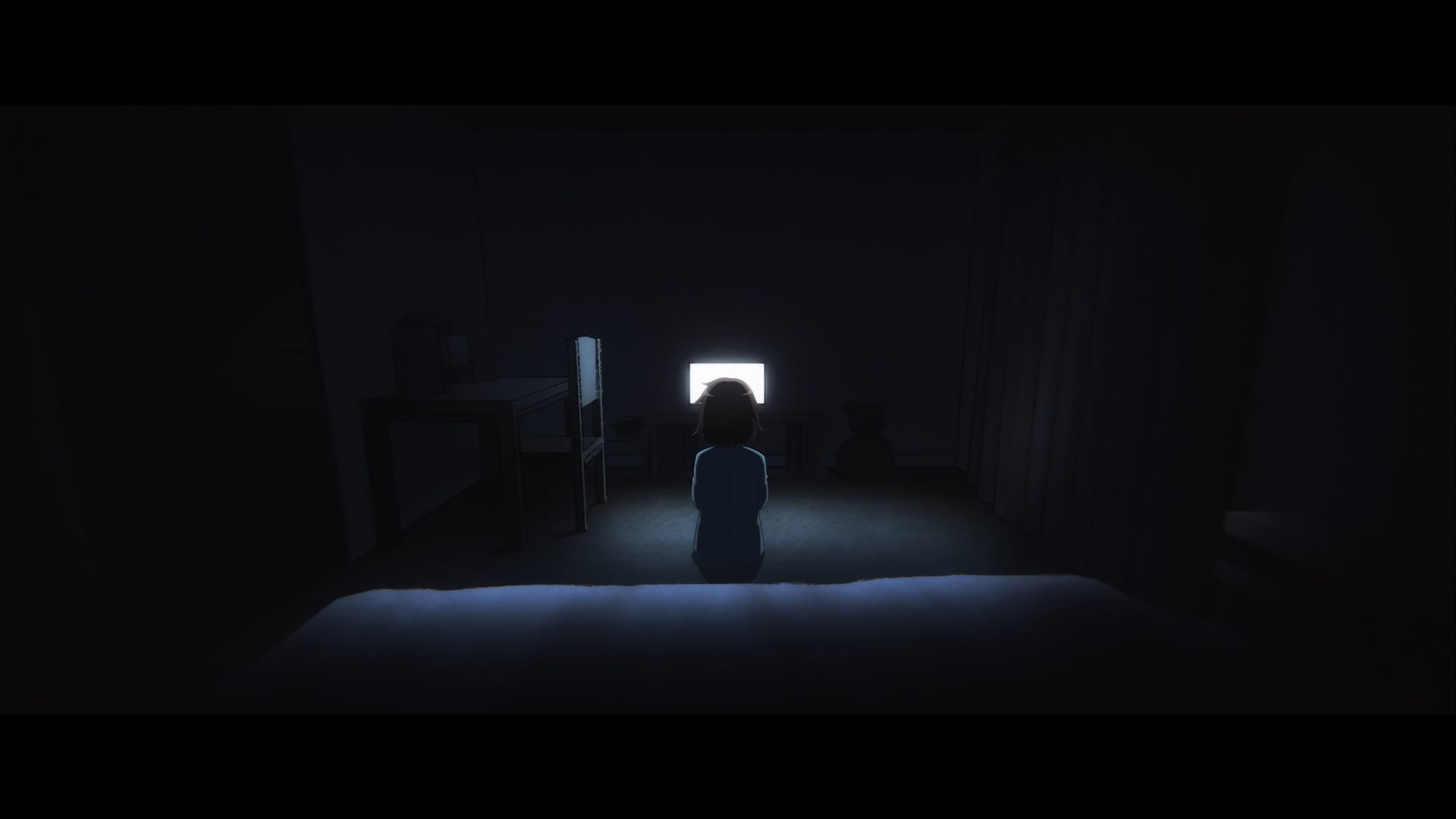

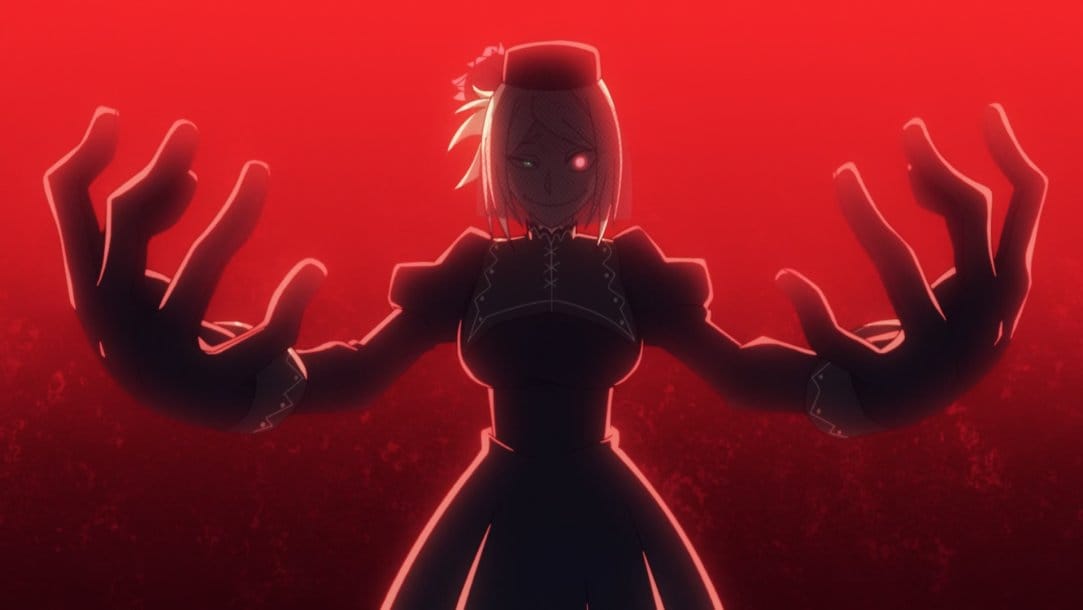

Modern Oonuma also isn't especially particular about the screen design in general these days, but there are still noticeable visual styles that he's fond of. One of the more easily identifiable is flat screen compositions that use a lot of negative space. Oonuma mentioned in a more recent interview that flat screen design was a big inspiration for him early on (go figure, he does play with a lot of it). Into the late 2010s especially, these flat screen compositions—instead of just silhouettes of characters on their own over a color or a standard background in the positive space like he was already privy to—take the form of contrasting light and dark sides like literal splits in halves, thirds, or fifths of the screen while the characters or their shadows appear to be melting into the other half. It's a unique approach to a shadow puppet-esque theatre look that is especially distinguished from Shinbo's and his earlier collaborators.

Stills from The Misfit of Demon King Academy (©Shu, Kadokawa Corporation / Demon King Academy; images 1 & 2), Fate/kaleid liner Prisma Illya: Vow In The Snow (©Hiroshi Hiroyama, TYPE-MOON / KADOKAWA / "Fate/Kaleid Liner Prisma Illya Movie" Production Committee), Fate/kaleid liner Prisma Illya: Licht - The Nameless Girl (©Hiroshi Hiroyama, TYPE-MOON / KADOKAWA / "Fate/Kaleid Liner Prisma Illya: Licht - The Nameless Girl" Production Committee), and Ragna Crimson (©Daiki Kobayashi / Square Enix, "Ragna Crimson" Production Committee)

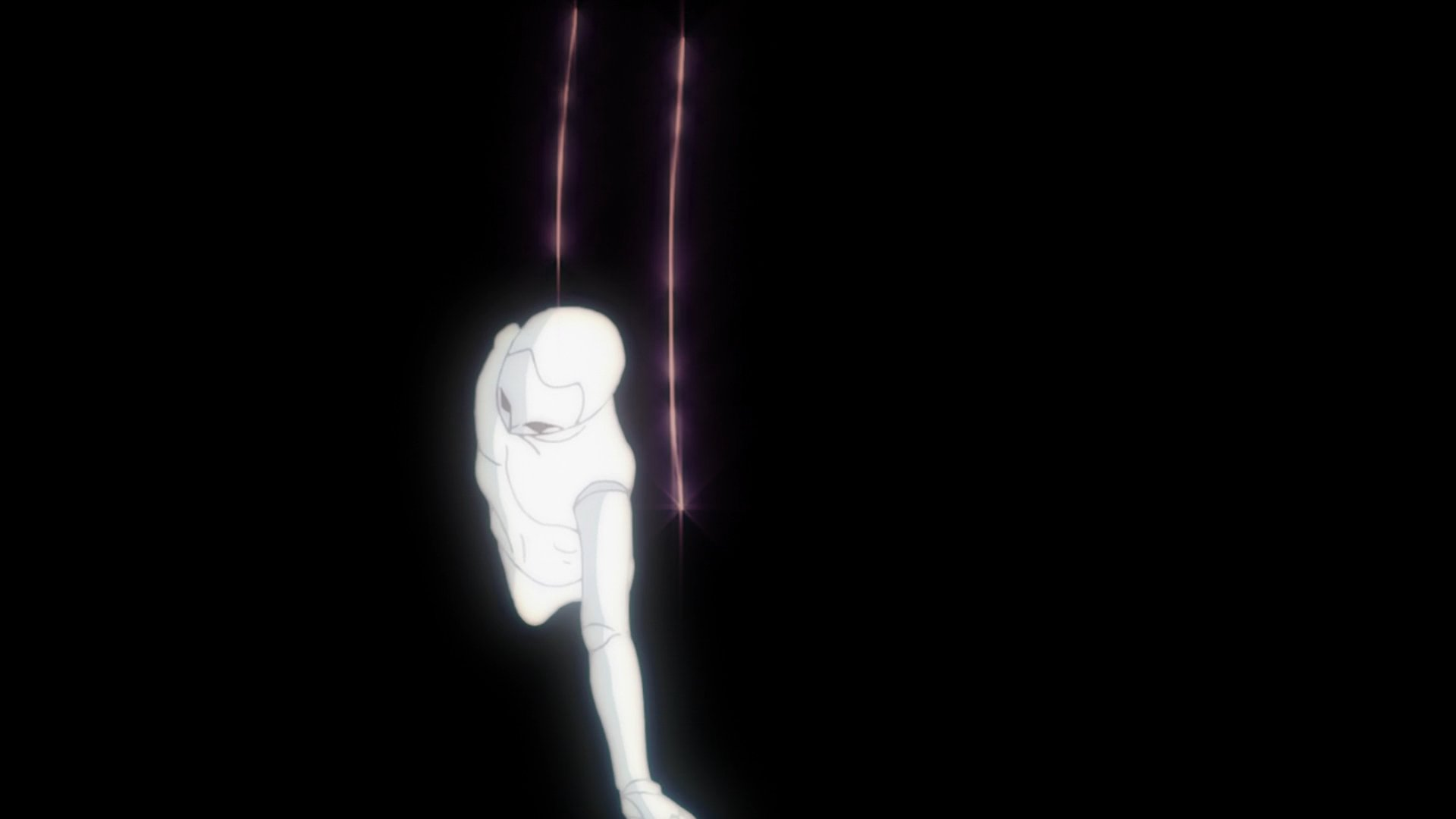

Oonuma's approach to the Fate/Kaleid movies has him far more involved than he was with the television versions. The first film, Vow in the Snow (2017), was solely directed by Oonuma. For a film, anime directors can be expected to be more involved in unifying its elements than a standard television series. Vow in the Snow shows a noticeably active participation by Oonuma who upended the series' entire visual identity. Contextually, the film technically picks up from the end of the fourth season (3rei) but is mostly a telling of past events. It's set in a different world, at a different point in time, with a different character as its main subject. "The tragic prequel."

Tragedy and loss aren't themes specific to this movie or 3rei, but these movies appeal more to drama than previous seasons. The screenplay still has its humor, but the general tone is quite different. The best comparison I can make for the visual difference is kind of like Oonuma being slightly inspired by Ufotable's Fate adaptations, but it's not trying to look identical or even super similar. It has a lot more put into the digital compositing, art direction, and general layouts compared to the TV version, but even if you compare this movie to some of the previous seasons, you might be surprised to find out that they have a lot of the same staff, like the director of photography. That's partially the "film budget/time" buff, probably, but there's also a different kind of intentionality at play.

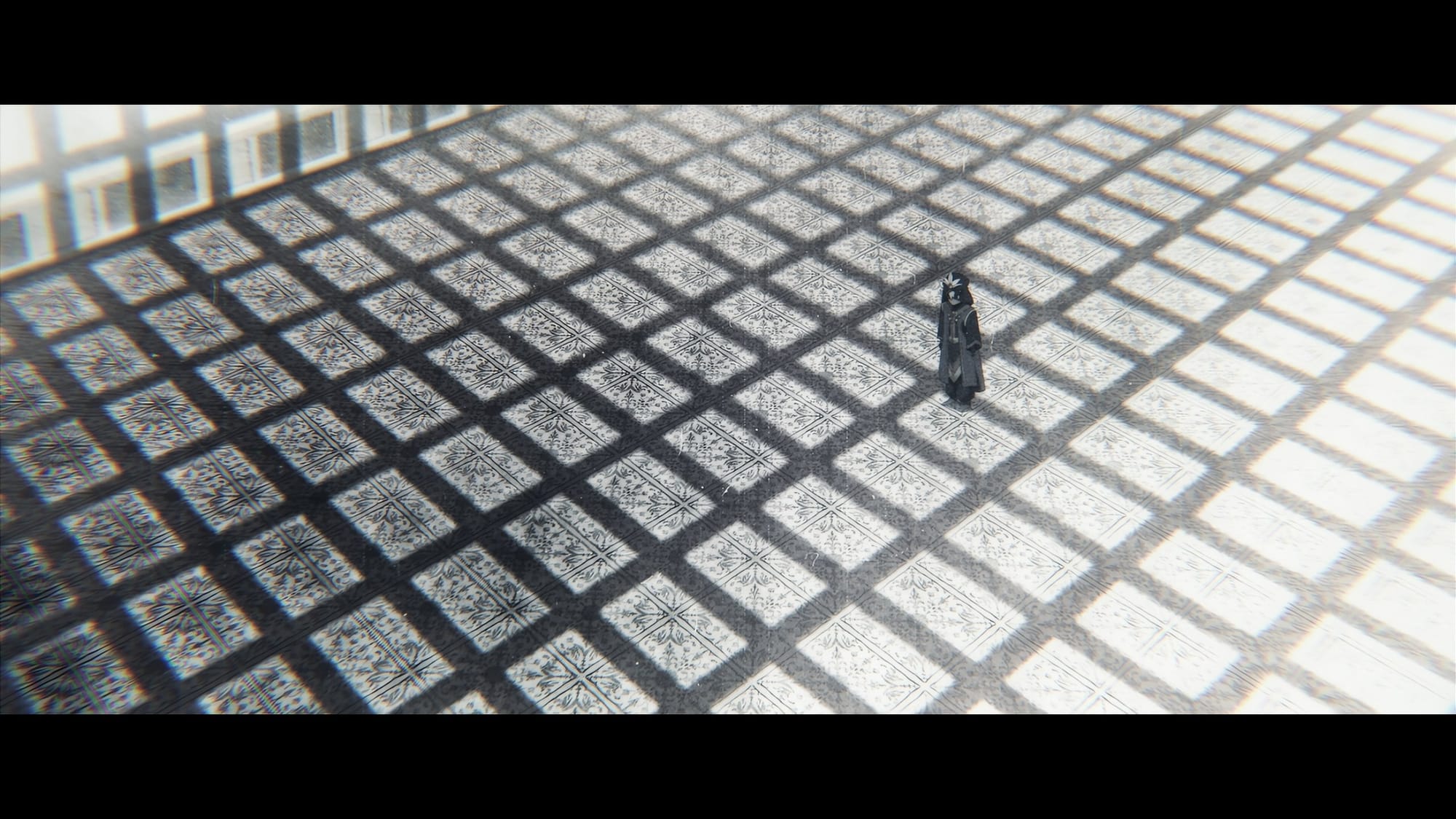

Fate/kaleid liner Prisma Illya: Vow In The Snow, ©Hiroshi Hiroyama, TYPE-MOON / KADOKAWA / "Fate/Kaleid Liner Prisma Illya Movie" Production Committee

With the exception of the flat shadow theatre-like parts, this movie's visual identity hinges a lot on perceptive depth. Shallow depth of field compositing, warped perspectives, 3D backgrounds, and generally wider angles are far more common in this entry than in others; as is the reverse in flatter screen designs that appeal more to a theatre look. The superficiality of the Ufotable comparison both starts and ends at the heavier photographic and 3D processing, because they're not alike otherwise.

Fate/kaleid liner Prisma Illya: Vow In The Snow, ©Hiroshi Hiroyama, TYPE-MOON / KADOKAWA / "Fate/Kaleid Liner Prisma Illya Movie" Production Committee

The second film from 2021, although not as technically ambitious as it sticks closer to the style of the television series and also seems to have had rather significant production issues, still pursues much more of Oonuma's specific charm. Binding window shadows on a sleeping character (similar to the motif of “chains”), parallax camera dollies, foreground objects physically separating characters, light flares, abruptly different art styles, appeals to minimalism, low angles, bird's eye views, fence/rail smacking, marionette (or mannequin) symbolism, aspect ratio shifts between 16:9, 21:9(?), and 2.35:1 are all employed—this is just a list of technical descriptions and ideas and it's totally superficial as "analysis," but it's fun to describe just because of how unassumingly numerous they are compared to the other director's takes on the franchise.

Fate/Kaleid Liner Prisma Illya: Licht - The Nameless Girl, ©Hiroshi Hiroyama, TYPE-MOON / KADOKAWA / "Fate/Kaleid Liner Prisma Illya: Licht - The Nameless Girl" Production Committee

Fate/Kaleid Liner Prisma Illya: Licht - The Nameless Girl (©Hiroshi Hiroyama, TYPE-MOON / KADOKAWA / "Fate/Kaleid Liner Prisma Illya: Licht - The Nameless Girl" Production Committee), Tsukuyomi: Moon Phase (©Keitaro Arima / Wani Books, Victor Entertainment)

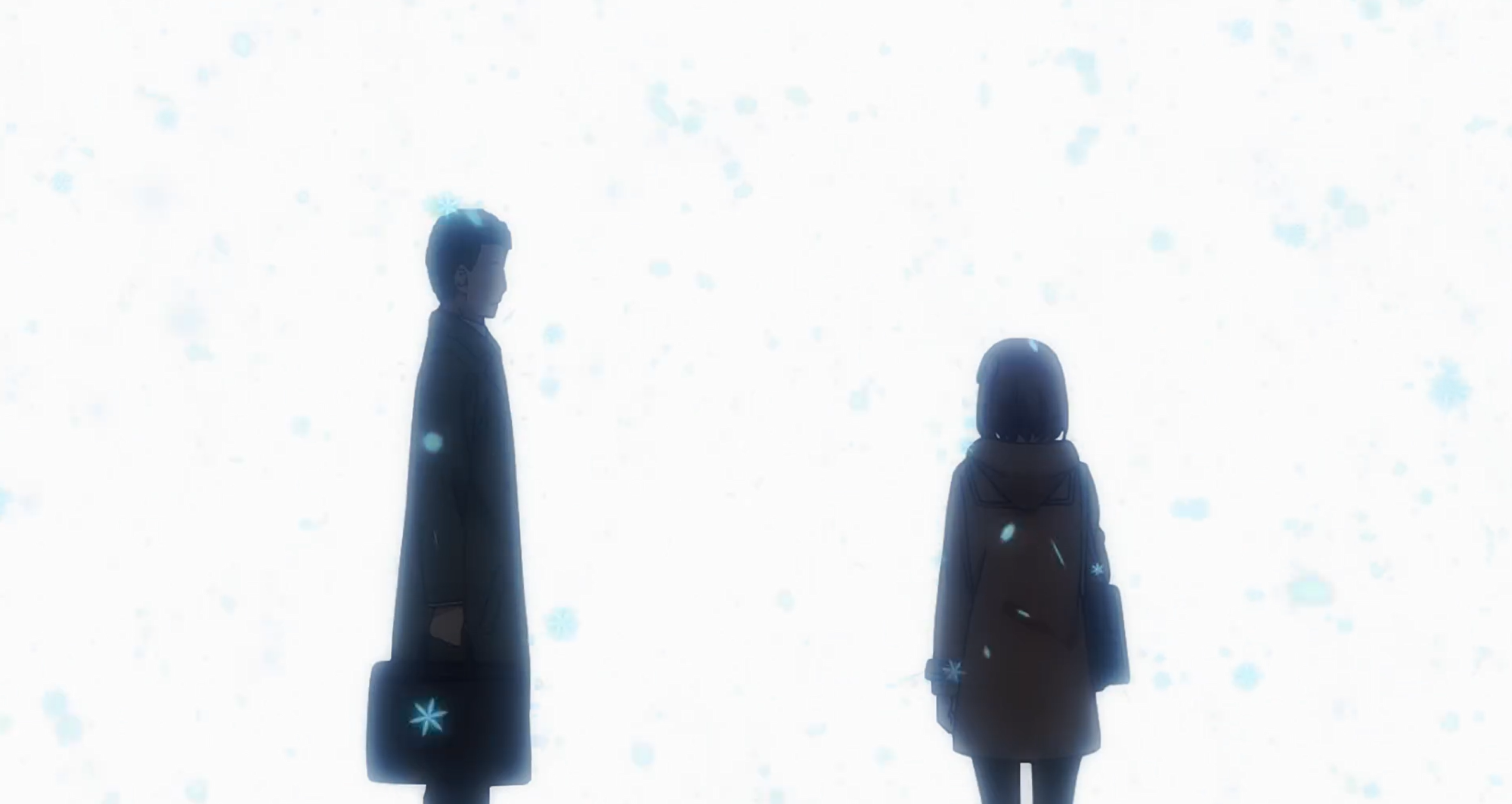

In 2018, Oonuma made a surprise guest appearance for a work produced outside of the SILVER LINK home base for the first time since Monogatari Series Second Season in 2013 with The Girl in Twilight. His involvement was surprising, but not difficult to explain: the show's director is the previously mentioned Jin Tamamura, who worked at SILVER LINK for a few years under Oonuma. The series remains rather niche, though it has many interesting ideas and some ambitious 3D action segments (presumably more-so handled by the show's series director, Yuuichi Abe, since then a consistent ally of Tamamura's) despite a limiting production.

This finale is about looking at pieces of a slowly built-up character and putting those pieces together as some sort of a whole. The protagonist, a cheery airhead with a strong personality, meets an alternate version of herself–a listless, stoic, and unmoving child–and they explore their background and go through a sequence of observing a broken girl (literally visually shown). It is exactly the kind of interpersonal character exploration that Oonuma excels at depicting via pure visuality. I don't know if Tamamura always had Oonuma in mind for this episode, but it makes sense why he would ask Oonuma to do it one way or another.

The Girl in Twilight, ©Akanesasu Anime Project

The Oonuma Effect: SILVER LINK

Oonuma's been around SILVER LINK for just about 15 years at this point, but only recently has SILVER LINK really started to promote in-house production assistants and animators to roles like storyboard artist and episode director. Before that, a majority of SILVER LINK's series directors were all outsiders who happened to get involved. Names like Kawatsura are commonplace actors by this point, but for the first few years, there weren't very many people outside of constant episode directors connected to the studio via studio Frontline origins like Jun Fukuta or the nowadays more storyboard-oriented Shinichi "Nabeshin" Watanabe. Oonuma has been a mentor of talent for staff going into and through the studio either way.

It wasn't until about 2012 that this 'mentorship' bore fruit through outside directors getting involved with the company. First and foremost, the prior Shuuji Miyazaki worked under Oonuma as SILVER LINK's first director-series director pair; and as mentioned, he was adjacent to Oonuma's style via their shared SHAFT connection.

Then there's Masato Jinbou. Jinbou was already a competently strong director by the time he came into contact with SILVER LINK and he worked with a number of different directors at the studio. He wasn't primarily working with Oonuma over others, and he was the series director for Masashi Kudou's short-form Kyou no Asuka Show (2012), and then was a series director for seasons 2-4 of Fate/Kaleid (2014-2016) under Oonuma, and was put in charge as solo-director of the Nozo x Kimi (2014) OVA, Shomin Sample (2015), and Chaos;Child (2017). He didn't carry much of Oonuma's specific flavors and is distinct in that he prioritizes pre-production from the screenplay stage, often writing the screenplay himself, as a mode of establishing a work's foundations. Although for a brief moment, Jinbou independently used geometric lighting and weird framing in, at least, Nozo x Kimi.

Nozo x Kimi, ©Wako Honna, Shogakukan / Anisun Project

The Girl in Twilight's Jin Tamamura also got involved with SILVER LINK in 2012 after he left Ankama Japan, and he ended up as the series director for three of Oonuma's projects from 2014 to 2017. I don't think Tamamura took much of Oonuma's style either, but his skills as a director definitely developed through his projects at the studio. There are times, though, especially in I Was Reincarnated as the 7th Prince So I Can Take My Time Perfecting My Magical Ability (2024-2025), where Tamamura's storyboards and/or direction evoke similar theatrical dramatics, especially in morphing the frame's negative space, camera angles, and switching art styles or entire mediums with similar atmospheres.

I Was Reincarnated as the 7th Prince So I Can Take My Time Perfecting My Magical Ability seasons 1 & 2, ©Kenkyo na Circle, Kodansha / "The Seventh Prince" Production Committee

Perhaps the most important member of SILVER LINK's league of directors alongside Oonuma is the pseudonymous Mirai Minato (湊未來). Minato's background remains unknown. The name is based off of a place in Yokohama named Minato Mirai, which is also their Twitter profile picture. Their first credit with the studio is in 2013– the same year they received series directing duty on Fate/Kaleid's first season with Miyazaki. It's not unheard of for young animators or producers to be promoted very fast into the role of "episode director", but starting off as a "series director" is basically never going to happen, which makes it seem like they either have some sort of lengthier background or assumed this name as they were promoted to director/joined SILVER LINK.

Another theory proposed by some is that it was originally a name used by SILVER LINK president Kaneko and later became a collective pseudonym like SHAFT's Fuyashi Tou or Sunrise's Hajime Yatate because of some "random" credits amongst Minato's portfolio, including a single key animator credit in 2014 and a credit as director of photography in 2019. The evidence is mostly circumstantial. Via his Frontline days, Kaneko has done a bit of animation and directing work under the pseudonym "Hayato" (隼人). Minato's Twitter account also followed Kaneko's now-defunct Twitter account but no other individual staff member's around a decade ago. The other part of this idea is that Minato is credited for a huge body of work, like in 2024 alone: director of Sasaki and Peeps, director and series composition writer for Mission: Yozakura Family, chief director and series composition writer for Hokkaido Gals are Super Adorable, alongside numerous screenplay, storyboard, and episode direction credits on all three of those series; and on top of that, a storyboard credit on a series produced by SILVER LINK's buddies at C-Station.

That is an incredibly large body of work to be in charge of even with assistant and series directors seeing how active Minato was in the episodes too. Minato's works are both diverse and highly inconsistent in aesthetics and quality, part of which may be due simply to their schedules and differences in core staff. Minato was promoted to director in 2017 with Masamune-kun's Revenge and from then on was a pillar of its directors, sometimes co-directing with or directing under Oonuma, or leading the charge by themselves and sometimes with their own assistant director. As of 2025, Minato is the only SILVER LINK director besides Oonuma to receive true "chief director" roles overseeing another director.

There does seem to be a little bit of Oonuma-isms in color and certain techniques here and there, at least assuming this isn't the product of staff who work often with Oonuma and have been influenced by him (or vice versa). There are points at which The Dungeon of Black Company feels like the most Oonuma-influenced work of Minato's catalogue, specifically in color and screen direction. Either way, this is a hard director to read because so little is known about them and who it is, and they do so many different things.

The Dungeon of Black Company, ©Youhei Yasumura, Mag Garden / Reisach Mining Detmold Branch

Yuushi Ibe (伊部勇志) is a bit of a wild card. A former production assistant from Sunrise, Ibe started directing in 2014 as a freelancer in and around SILVER LINK and other studios. Ibe has worked with Oonuma now and then as an episode director, but his strongest influence is probably from Minato seeing as he works on their series a lot and ended up as their assistant director for five of Minato's series between 2021 and 2024.

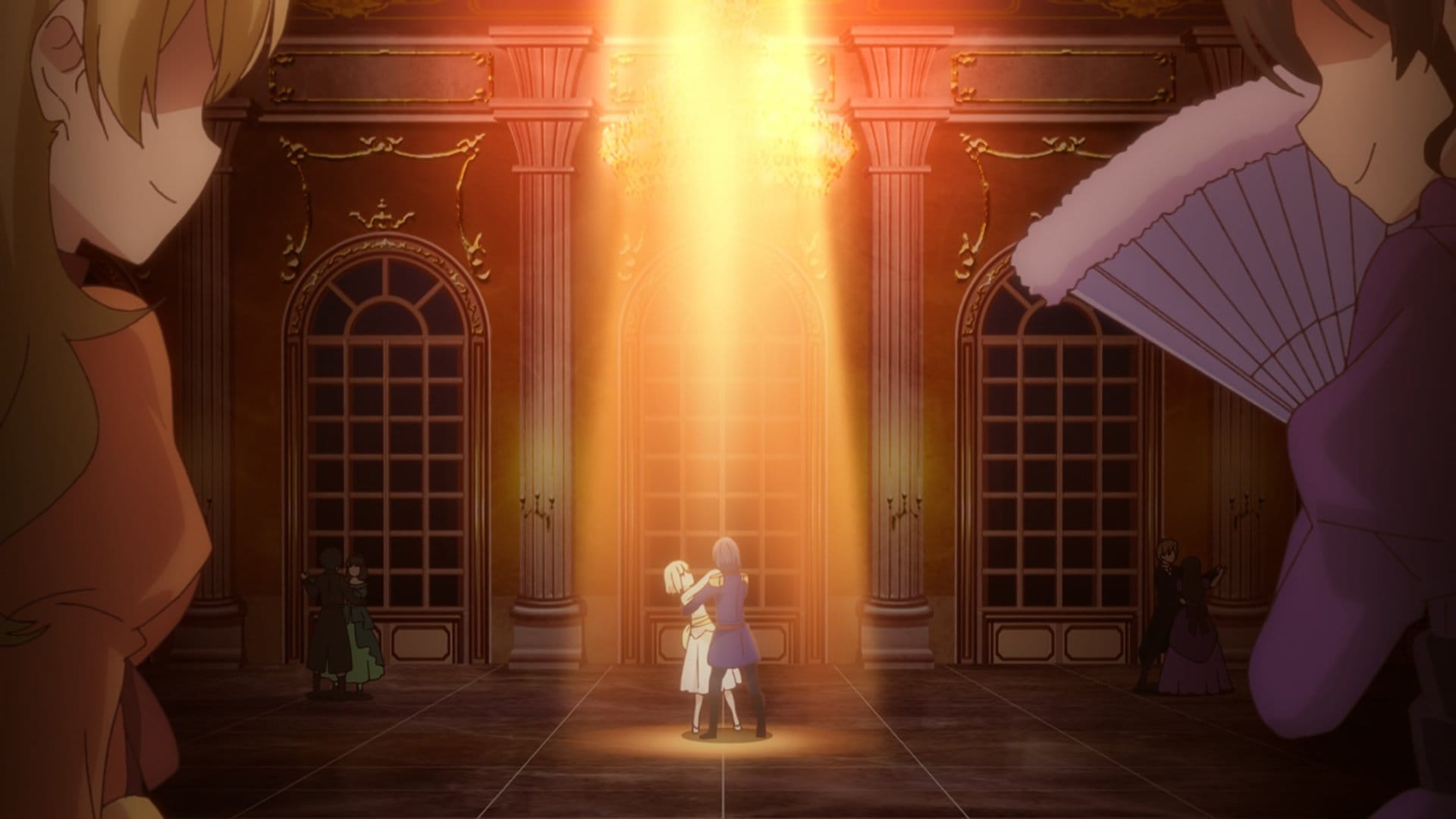

I'm not sure about including Ibe on this list because I don't consider him to be directly Oonuma-influenced, but he does have a recognizable and categorically similar approach. His solo-directorial debut, Tearmoon Empire (2023), shows him as a force of nature directing and storyboarding 3/4 of the first four episodes on his own and with a clear identity utilizing colors, composition, and various art styles.

Tearmoon Empire, ©Nozomu Mochitsuki, TO Books / Tearmoon Empire Production Committee 2023

He's taking certain scenes and going at them with certain color schemes in mind. He's using picture book and harmony frame styles, and he's not afraid to use more complex photography and 3D processing for still-camera backgrounds or ambitious ballroom dancing, cutting back and forth between 2D close-ups and 3D spinning, revolving crowd, and moving subject shots. Of all of SILVER LINK's associated directors, Ibe seems to have the most theatre-like staging. He's often crossing between very flat images with texture and open 3D-assisted layouts or simply wider angles.

Tearmoon Empire, ©Nozomu Mochitsuki, TO Books / Tearmoon Empire Production Committee 2023

Masafumi Tamura (田村正文) is a director with... funny circumstances...? He's a "SILVER LINK director", but he's affiliated with C-Station. Tamura is a "SILVER LINK director" because he basically only directed for SILVER LINK productions for a long time. All of his works as director bar his upcoming Chained Soldier 2 at Passione have been produced by SILVER LINK. He handled some gross outsources and directed a few episodes of things like Dragonar Academy (2015) at C-Station, but he's never directed a C-Station series, and he debuted as series director on Ange Vierge (2016) at SILVER LINK, which C-Station had no other part in.

The gross outsources Tamura was handling included things like Fate/Kaleid and even other studio's works, but he did his first three series at SILVER LINK as solo works: Ange Vierge, Two Car (2017), and Wise Man's Grandchild (2019). According to him, he never had a proper directing mentor or teacher. Tamura is a hard worker doing storyboards, episode direction, key animating, and also oftentimes doing animation direction work– all while still being the series director. Tamura developed his style of directing basically independently, but Oonuma ended up filling a "mentor" role to a point as they worked together on The Misfit of Demon King Academy.

What Tamura takes from Oonuma largely isn't a "visual style", but probably something along the lines of directing philosophy, efficiency, or ways of thinking about direction. What Tamura says about working with Oonuma isn't that he's developed a similar taste, but rather that he simply learned a lot from Oonuma.

On the other hand, Keisuke Inoue (井上圭介) is a director who feels like he's absorbed the essence of Oonuma as a sort of protégé. A while back I mentioned "a rookie director" in charge of co-directing episode 3 of Chivalry of a Failed Knight–that's Inoue. Inoue comes from a background in 3DCG, specifically from Studio DEEN's 3D sub-studio Umidori. He joined SILVER LINK sometime ~2013 and did a bunch of miscellaneous jobs: CG for Kawatsura's show, he was a setting manager for Fate/Kaleid, he did 3D layouts and episode direction on one of Jinbou's shows, he directed the Fate/Kaleid short DVD specials, and he developed to the point that Oonuma seemingly chose him to direct the first episode of Anne Happy (2016) alongside doing 3D layouts and being given his own episode to storyboard and direct. In 2017, he was promoted to assistant director under Minato and was given responsibility for his own project in 2019.

Ao-chan Can't Study!, ©Ren Kawahara, Kodansha / Ao-chan Can't Study! Production Committee

The opening to Ao-chan Can't Study is really different from other directors at SILVER LINK because his color decisions are highly reminiscent of Oonuma. It might not directly be Oonuma's influence that led to this opening having visible lyrics as a part of the screen composition or using an Oonuma-like color style, as it could be entirely coincidental, but it's in line with the kinds of things Oonuma does with the added aspect of Inoue's knowledge in 3D proficiency, showing off. The comedy aspects of the series switch between styles, where nearly photorealistic pictures of animals pop up as metaphors for animalistic perverts or just goofy drawings, but then the show also has its delicate intricacies that take moments to focus on Ao-chan as a character, as herself, and not just as a pervert for a single running joke.

Inoue "left" SILVER LINK after that series, but that's in quotes because he's freelance and still sticks around them. He's only become a more indulgent, experimental director since then, too. His next project was My Next Life as a Villainess: All Routes Lead to Doom! (HameFura) in 2020 and 2021 where it's clear as day that he's made other parts of Oonuma's style his own like the repeating screens of a single character bust in the opening. He digs deep into the introspective drama of a reborn-in-another-world girl's past life with all of its heavy emotional baggage. Character relationships, feelings, and story beats are not-so-subtly presented in full flesh and blood through Inoue's visual languages as he developed basically in real-time across the show's two seasons. In season 2, he wrote, storyboarded, and directed an episode, which gave him full power to stage and do things in an even purer form of himself (see images 4-6 below), which came in the effect of uniquely powerful motifs and storytelling.

HameFura, ©Satoru Yamaguchi, Ichijinsha / HameFura Production Committee

And he does this with an expert craft again and again in Level 1 Demon Lord and One Room Hero (2023) and the HameFura Movie (2023). Regardless of what absurdity might be going down as a chibi devil finds itself swapping genders for a burnt-out depressed ex-hero or following the rebirth of a girl intending to ensure that she doesn't get snatched into a death sentence according to her video game's logic, Inoue finds and makes sure that there is a human story to express. There is some sort of beauty in tragedy. His works tend to have that kind of expression.

Level 1 Demon Lord and One Room Hero (©Toufu, Houbunsha / Level 1 Demon Lord and One Room Hero Production Committee); HameFura (©Satoru Yamaguchi, Ichijinsha / HameFura Production Committee)

Ken Takahashi (高橋賢) is an animator with a pretty big portfolio. Early on, he started doing animation work for SILVER LINK and was given the opportunity to direct a promotional OVA for the Kirakira visual novel in 2013. He stuck around and started storyboarding and directing episodes of Fate/Kaleid, but people into "sakuga" know him for his animation first and foremost. Of course, he ends up as the action director or special effects director for a bunch of SILVER LINK works, including Fate/Kaleid, until he was added to its fourth season, 3rei, as one of the directors under Oonuma. In 2018, he made his debut as a solo TV director with Butlers x Battlers, which Oonuma handled an episode of, and then he expanded his directing work to Ufotable's Heaven's Feel trilogy (as a unit director), Sword Art Online: Alicization, Jujutsu Kaisen, and so forth. In 2021, he came back to SILVER LINK as the assistant director, CG supervisor, special effects animation director, and some other roles for the second Fate/Kaleid movie.

Takahashi's work up until this point doesn't feel like it has much of an Oonuma-like flavor, especially Butlers x Battlers, where it's hard to find Oonuma's flavor even from Oonuma himself (it's a show with a lot of problems). Considering how lax Oonuma was for the Fate/Kaleid television series, that probably makes sense. He was also a unit director on the first Fate/Kaleid movie, but being so involved with the second film may have changed his perspectives a bit. Takahashi was chosen as the director of Ragna Crimson and compared to his work at other studios up until that point and Butlers x Battlers, it's really different. Takahashi seems a bit like Inoue in that he forms a raw, visceral language that he wants to speak with; but it's not at all the delicate, bittersweet prose that Inoue has. Instead, Takahashi presents power and violence birthed through love. If that makes sense? I guess that is Ragna Crimson, though, isn't it?

With only two series under his belt, it's difficult to say exactly what qualities are the result of Ragna Crimson itself and he's internalized as methods he likes to do things, but he has another upcoming series.

Ragna Crimson, ©Daiki Kobayashi, Square Enix / "Ragna Crimson" Production Committee

Lastly, there's Yuusuke Sekine (関根侑佑), the youngest of the three early in-house animators at SILVER LINK promoted to directors at the turn of the decade (those being himself, Yamato Oouchi, and Takahiro Nakatsugawa). Sekine is different from the other two in that he sticks very close to Oonuma. Nakatsugawa is a bit of a wild card, but he's shown himself to be good at action and drama. Oouchi isn't so great at action, but he works closely with Minato and was promoted to assistant director in 2025 for April Showers Bring May Flowers. Oouchi and Nakatsugawa rarely show up for Oonuma's specific projects, with the former sticking close to Minato; meanwhile, Sekine has mostly stuck to Oonuma's projects and as of Deep Insanity in 2021 is often entrusted with the first episodes of Oonuma's works.

Then, in 2023, Sekine and Oonuma directed episode 8 of Ragna Crimson together with Akira Nishimori's storyboards. This could've fit as information earlier when discussing Oonuma's continued creative spurts, but it feels more natural to discuss Sekine alongside it. Presumably, the episode's A-part (the first half, images 1-3 below) was handled by Sekine, with the latter part (images 4-6) done by Oonuma. This assumption comes from the fact that the B-part has much heavier, varying photographic processing, which feels like something Oonuma might do; though, the credits are also ordered that way.

Ragna Crimson, ©Daiki Kobayashi, Square Enix / "Ragna Crimson" Production Committee

That's not the only time Sekine and Oonuma tag-team an episode. They do it again for The Misfit of Demon King Academy II episode 13, the first episode of its second cour in 2024.

The Misfit of Demon King Academy II Part 2 (©Shu, Kadokawa Corporation / Demon King Academy)

Lo and behold, Sekine was then not only given the responsibility of directing and storyboarding the first episode of Oonuma's Princession Orchestra, but he was also promoted to assistant director. Regarding his work on the series, Oonuma called Sekine the "Minister of Lip-Syncing" humorously.

Oonuma is vastly underappreciated for his work. He’s in a different environment from 15 years ago, he’s under different circumstances from 10 years ago, and his material is always changing. Shin Oonuma may be the least recognized of “Team Shinbo” for artistic indulgences, but he is undoubtedly an essential part of both SHAFT and SILVER LINK's histories.

Author and cover illustration: Sarca

Editing assistance: Tamara Lazic

Further reading:

- Animage. (2005). Animage February 2005/Vol. 320. Tokuma Shoten.